New Zealand Airshow Display Teams

The Red Checkers

This team formed in 1967 from instructors from the Central Flying School and Pilot Training Squadron initially to display their Harvard trainers at the airshow held to mark the 50th Anniversary of flying from RNZAF Wigram's airfield. They were essentially a continuation of the CFS Wigram team but with a new barnd and image, and they continued on their predecessor's tradition, which continues right through till today.

In 1973 the team was disbanded for some years due to the oil crisis preventing the extra flying, with at least one failed attempt to revive the team in 1975. They did eventually reform in 1980 to practice and lead up to the 1981 season, and the Checkers have continued as one of New Zealand's most popular display teams since. You'll find more of the team's history revealed by many of its members below.

The team has used three aircraft types since its formation - North American Harvards from 1967 to 1973, New Zealand Aerospace Industries CT/4B Airtrainers from 1980 to 1998, and the Pacific Aerospace Corporation CT/4E (an updated version of the CT/4B but with a more powerful 300 Horsepower Continental IO540 engine)

Note: The code (s) denotes the team's solo performer

1960's __ 1970's __ 1980's __ 1990's __ 2000's

Display Dates Venue Pilots Position 5th of Nov 1967

______________

_

_Wigram Airshow

Marking 50 Years of

Flying Training at

_______Wigram_______Flt Lt Thomas S. Lambert

Flt Lt Roger Henstock

Flt Lt Robin Klitscher

Fg Off Dick Metcalfe

Flt Lt Ken Gayfer

No. 1

No. 2

No. 3

No. 4

No. 5 (s)

Note:

The Wigram airshow was the first display for the CFS team under new identity"The Red Checkers." They seem to have been put together just for this airshow and then another new team formed later in the year under Robin Klitscher for the 1967-68 summer season.

A huge thanks to Robin Klitscher and Ken Gayfer who have both contacted me and provided some excellent insights into this 1966-67 inaugural 'Red Checkers' team, of which they were members.

Robin Klitscher writes:

"I can confirm that the occasion was indeed the first under the banner "Red Checkers". I recall it well, though not entirely for the aerobatics. There had been some resistance to singling out the team under such a name - it was seen as elitism, otherwise a manifestation of the instinct in this country not to tolerate heads raised too far above the parapet.

We had also arranged to have the engine cowls of the aircraft done up in red checks - Red Checkers. This was just forgivable. But in addition we'd had our issue flying suits (in drab grey) dyed red in keeping with the team name. This was absolutely unforgivable - tall poppies gone mad, and an insult to government property! Oh, well - as they would say today, get a life.

It was Ken Gayfer who coined the 'Red Checkers' name and theme. He recalls:

"I was the originator of the name Red Checkers and the designer of the ‘patch'. Whilst brainstorming one night at a restaurant I came up with the name which is the combination of two inputs. RAF CFS instructors are, or used to be, informally called ‘the checkers' (and some other less charitable epithets) because they carry out routine upgrading of flying instructors and random checks on instructors standards.

Whilst I was doodling on a paper napkin, I drew a plan view of a Harvard formation of a box, plus one in line astern, and shaded in the definition of the red wingtips and tail sections. I saw that this formed a loose checkerboard pattern and the association of ideas relating to us as RNZAF CFS ‘checkers' seemed like an obvious play on words at the same time as describing the appearance of the checkerboard pattern in red and silver. It's amazing what a couple (?) of glasses of red will do for the imagination!

The design of the patch is derived from an adaptation of the spectator's view of our last manoeuvre which Robin described where the team of four flew towards the crowd and I came from behind and flew in opposing direction between leader and number two whilst the four were commencing a fan break."

See the patch above this team entry - the Red Checkers team still uses it today some 40 years later.

Meanwhile Robin recalls some memories of what the display routine was like:

"As far as the routine goes, I recall writing a paper at Wigram about how the aerobatics team should look. Its theme was "patterns in the sky". I'd probably be thoroughly embarrassed to read it again now, however.

In the Harvard of course there were strict limits to what was possible, so most of the manoeuvres were pretty standard. The addition of the No's 4 and 5, however, (a tale in itself) did open things up a bit. Particularly with smoke, the No 5/solo man could fill in while the rest of the team was scrabbling to regain height lost in the preceding manoeuvre, and vice-versa.There was also the potential for opposed passes, one of which formed the culmination of our show - the team doing a fan break with smoke toward the crowd, and the No 5 appearing from behind the crowd, also with smoke, pulling up and through the fan break. It looked good, but took quite a lot of practice to get right."

Harvard Team in Box Loop - A First

"Prior to the Lambert team, it was not considered possible to loop four Harvards in box formation for display purposes. The No 4 in the box and at slightly greater loop radius, it was said, had insufficient power to stay with the formation. But as Gavin Trethewey recently confirmed, the early Lambert team had proved this wrong. It was possible - though only just. Subsequent teams carried it on as an essential part of their routines.The leader had to fly a very consistent loop, using only partial power so the No 4 could stay with him, but enough power and speed not to make things embarrassing for the wingmen in echelon over the top. What was usually necessary was for the No 4 behind and below the leader to get ahead of the game a bit, and sneak up on the leader so that over the top, when he would be at full power and dropping back, he didn't lose the entire formation.

It was a bit of a kludge, but it worked - though again, only with lots of practice. We carried this trick on after Tom left, of course, and I can remember as leader doing lots of sorties just as a pair in line astern working things up. I also recall on occasion catching sight of the No 4's propeller and cowl *ahead* of my sightline past the leading edge of the wing as we went over the top, which could be a bit scary!"

Deploying to an Airshow

"And yes, when we travelled we did have a significant retinue of support from technical crews, and our Devon cousins. Also a spare Harvard. The effort was quite considerable, really."

Roger Henstock remembers:

"The team became the "Red Checkers" in late 1967. I took part in some of the discussion regarding the renaming of the team but I was only a relatively junior officer and an instructor at PTS so I wasn't very influential in these matters. I remember being impressed how quickly the team badge, the red flying overalls, the team scarf and red and white checkered nose cowls was arranged.

I was posted back to No. 75 Squadron as an instructor on Vampires in December 1967. In the two years I was a member of the team I flew 111 Harvard displays and practice formation aerobatics sorties. There were many more positioning sorties. For thse two years instructors at Wigram were kept busy producing pilots because of the Vietnam War and many of our practice sorties were performed before and after "normal work."

Robin Klitscher went on to command No. 3 Squadron, serve in Vietnam and then rise to the rank of Air Vice Marshall, where he became Deputy Chief of Defence Staff. He retired from the RNZAF in 1993.

Ken Gayfer went on from CFS to No. 75 Squadron where he became Training Flight Commander on Vampires, and he also joined the No. 75 Squadron "Yellow Hammers" display team. He then went onto A-4's in the USA and in NZ, and lead the first RNZAF Skyhawk display team. He eventually rose to the rank of Air Commodore.

Thomas Sydney Lambert was awarded the Commendation For Valuable Services in the Air (cvsa) in 1967 for his leadership of the school and the team. The citation read,

"Flight Lieutenant Lambert has served as a pilot since he joined the RNZAF in 1953. While holding the appointment of Flight Commander at the Central Flying School at Wigram, he trained and lead the formation aerobatic team of Harvard aircraft. This team under his leadership performed displays of outstanding merit and proved that formation manouvres, hitherto thought to be impossible, were possible of being performed to display standards."

1968 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard2nd of Mar 1968

_8-9 March 1968

13th of Apr 1968

_21st of June 1968

Greymouth Industries

and Agricultural FairRNZAC Pageant, Invercargill

Marlborough Aero Club

40th Anniversary, OmakaWings Presentation, Wigram

Flt Lt Robin Klitscher

Flt Lt John Hosie

Flt Lt Ross Ewing

Flt Lt Bruce Johnston

Flt Lt Ken Gayfer

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

No. 5 (s)

Above: The 1968 Red Checkers Team

Photo submitted by Ross Ewing, he says "This is Robin Klitscher's Team; the photo is dated 29 Jan 68. From left to right are: Robin Klitscher, John Hosie, Ross Ewing, Bruce Johnston and Ken Gayfer. We were all Flt Lts."Notes:

Of the 1967-68 team, Robin Klitscher recalls:

"Our first display with that team was on 3 March 1968, at Greymouth (I forget the occasion, but not the event).There were also two displays in Invercargill, on 8 and 9 March 1968, for the RNZAC Pageant (I recall that the weather obliged us to limit these to "flat" displays under a low cloudbase).

On 13 April we displayed at Omaka, for the 40th Anniversary of the

Marlborough Aero Club.

There was nothing more through the winter, and I was posted to helicopters at the end of that year. My logbook does record, however, a series of formation aerobatic sorties in November 1968, but with no associated display. These flights would most likely have been a workup for the replacement team that was to follow "

1968-69 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard_22nd of Feb 1969

RNZAC Pageant, Tauranga

Flt Lt John Lanham

Flt Lt Larry Olsen

Flt Lt John Hosie

Flt Lt Douglas Lloyd

Peters

Red 1

Red

Red

Red

Red __

_

visit to RNZAF Base WigramFlt Lt Larry Olsen

Flt Lt John Hosie

Flt Lt Graham Lloyd

Flt Lt John Denton

Flt Lt Angus Kingsmill

Red 1

Red

Red

Red

Red

1969-70 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard6th of Mar 1970

7th of Mar 1970

13th of Mar 1970

15th of Mar 1970

_

_

_

_18th of Apr 1970

RNZAF Ohakea

RNZAC Pageant, Wanganui

RNZAF Woodbourne

Display for

HM Queen Elizabeth II

at Picton (this was the first

RNZAF aerobatic team

to perform for the Queen)RNZAC Pageant, Masterton

Flt Lt Larry Olsen

Flt Lt John Hosie

Flt Graeme Goldsmith

Flt Lt Douglas Lloyd

Flt Lt John Lanham

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Notes:This display season saw the introduction of the RNZAF's new training colour scheme on the Harvards. The new colour scheme consisted of the Dove Grey and International Orange colours replacing the previously used Silver and Dayglo Orange scheme.

Graeme Goldsmith remembers a particularly exciting practice during this season:"I should add that a couple of days before the Queen's show we had a mid-air which caused damage to Olsen's, Hosie's and Lloyd's aircraft, which from memory all needed replacement as repairs could not be effected in time. Essentially, we normally practiced in the safe confines of the Wigram Training area and used the old satellite airfield of Birdlings Flat as our training reference.

However, on this particular practice we went out to the civilian training area at Brighton Beach with its less familiar ground features. From memory we had completed one routine and were into the second when a light aircraft from Harewood appeared immediately above just as the four was about to break into the "Bomburst".

As was normal for most looping manoeuvres No.4 had positioned forward and under Lead. Separation at the break for this manoeuvre was ensured by Lead maintaining the "G" loading while No. 4 relaxed slightly then rolled through 180. No's 2 & 3 Rolled 90 respectfully.

Unfortunately the presence of the 'lighty' caused Lead to relax the 'G' to avoid what he thought was going to be a collision, just as the break was called. Consequence? Lloyd rotated hitting Olsen's tail and jamming the rudder, and then Hosie's wing, gouging a reasonable slice out from underneath. First I knew of a problem was no-one was around as I came out for the cross over, and then plenty of chatter as Lead checked that everyone was alright.

We recovered to Wigram individually, albeit monitoring those that were damaged, and the maintenance folk then set to work to get some usable "smoke" birds for Picton. They did a great job as not all Harvards were modified to take the smoke kit. I'm not sure the show was our greatest as a rip-snorting north-wester created severe turbulence (as bad as I ever experienced) and caused some positioning problems in the narrow confines of the bay - still we got through."

This collision occured on Wednesday afternoon, the 4th of March 1970. A court of Inquiry was convened at Royal New Zealand Air Force Base Wigram, consisting of Squadron Leader Richard Lawry as president and Flight Lieutenant D. I. Lamason as the member.

1970-71 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard25th of Feb 1971

27th of Feb 1971

RNZAF Woodbourne

RNZAC Pageant, Nelson

Sqn Ldr John Hosie

Flt Lt Ross Lamb

Flt Lt Graeme Goldsmith

Flt Lt Douglas Lloyd

Flt Graham Lloyd

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Note:Graham Lloyd and Doug Lloyd were twin brothers

Graeme Goldsmith says, comparing to the excitement of the season before, "Nothing out of the ordinary for this crowd - just the usual run of air shows."

Regarding the scant number of displays Graeme adds: "A lean year. There may have been more, but I left Wigram mid-year for a FAC tour in Vietnam."

1971-72 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard26th of Feb 1972

5th of Mar 1972

18th of Mar 1972

Taumarunui

Hamilton

Oamaru

Sqn Ldr Don R. Smith

Flt Lt Ross Lamb

Flt Lt Ian A. Wright

Flt Lt Doug S. Lloyd

Sqn Ldr John L'Eef

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Notes:The team's positions wereas follows:

Sqn Ldr Don R. Smith, AFC (Leader)

Flt Lt Ross Lamb (Starboard wing)

Flt Lt Ian A. Wright (Port wing)

Flt Lt Doug S. Lloyd (Box)

Sqn Ldr John L'Eef (Solo)As well as the three official displays listed, Ian Wright says the team did five other displays at military bases - three at Wigram, one at Ohakea and one at Woodbourne.

The following photos from the Red Checkers 1972 season have been kindly supplied by Ian Wright:

The Red Checkers Team 1972

A close up from the team photo. Left to right are:

Ross Lamb, Doug Lloyd, Don Smith, Ian Wright, John L'Eef

Box Four Loop performed in February 1972 (RNZAF Photo)

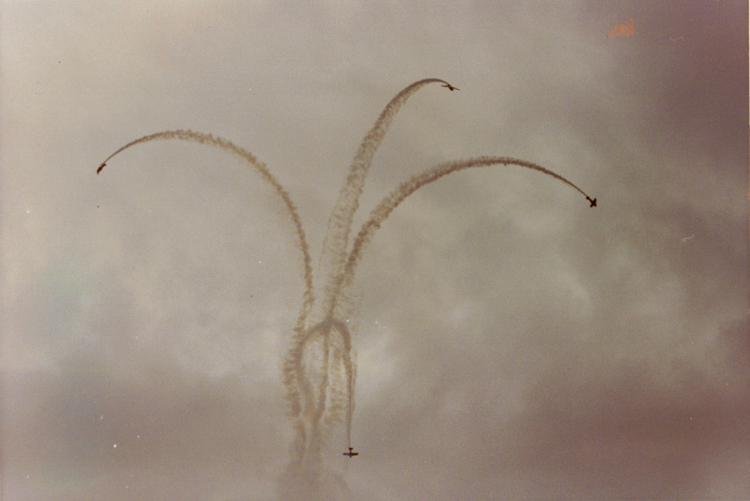

Upward Bomb Burst, February 1972

The 'Upward Bomb Burst' was followed by the

'Thread the Needle' manouevre seen aboveOf the Red Checkers, Ian Wright says:

"The first time I saw the Red Checkers was at the Wanganui RNZAC Pageant, 7th of March 1970, at which my contribution was a demonstration of a Sioux light helicopter. I was startled and stunned by the display of Larry Olsen's team, so I was rather nervous when approached by Don Smith to gauge my interest in joining the '72 team.

Red Checkers teams had a high proportion of jet pilots whose bread and butter was formation flying, and I had come to Wigram from 5 years of Auster and Sioux operations in a battlefield support role, and been training Army pilots in Sioux and Airtourers for 18 months before moving to CFS. Maybe it showed, but once locked into formation the adrenaline and hard physical work soon took over, and it was all in place by the time it was my turn to startle and stun my family who came to the March '72 pageant at Hamilton. Those days of tight Harvard formations with deafening propeller tip shockwaves were hard to beat as a spectacle.

Red Checkers teams come and go, but looking back, it is interesting to see the connections over time. I joined the RNZAF with Ken Gayfer and Larry Olsen. Robin Klitscher was my first captain on Sunderlands in Fiji and trained me as a QFI, and I was OC Flying Training Wing when Frank Sharp was tasked with getting the first Airtrainer team together. My first flight in a Skyhawk T-bird was with Ross Ewing, who tucked into formation then handed control to me with the comment that as Red 3 I ought to be comfortable!

The more modern aircraft used these days may not have the sheer impact of a team of Harvards, and the Airtrainer didn't have much power for solo aerobatics let alone in formation, but they are no less challenging in their own way, and a great way to maintain the professionalism that is the hallmark of the RNZAF. It's great to see that the Red Checkers have not become yet another asset to fall victim of “economy”."

1972-73 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard25th of Feb 1973

10th of Mar 1973

16th of Jun 1973

Ashburton

New Plymouth

Air Force 50th, RNZAF Station Wigram

Sqn Ldr Don R. Smith

Flt Lt Gary A. Ritchie

Flt Lt Ian A. Wright

Flt Lt Barry J. Mitchell

Flt Lt Ces Crook

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Note:Team positions were thus:

Sqn Ldr Don R. Smith, AFC (Leader)

Flt Lt Gary A. Ritchie (Starboard wing)

Flt Lt Ian A. Wright (Port wing)

Flt Lt Barry (Mitch) J. Mitchell (Box)

Flt Lt Ces Crook (Solo)As well as the two public displays listed, this team also did two other displays at RNZAF Base Wigram.

Following the 1973 Red Checkers season, which was short in itself, the oil crisis saw to it that no team was formed for the 1973/74 summer season. However the Checkers did reform in November or December 1974 for a 1975 season

The following photos from the Red Checkers 1973 season have been kindly supplied by Ian Wright:

The 1973 Red Checkers Team

Left to right are Barry Mitchell, Ian Wright, Don Smith,

Ces Crook and Garry Ritchie

The 1973 Red Checkers Team with their Harvards

A closer look at the above photo:

Left to right are Barry Mitchell, Gary Ritchie, Don Smith,

Ian Wright and Ces Crook

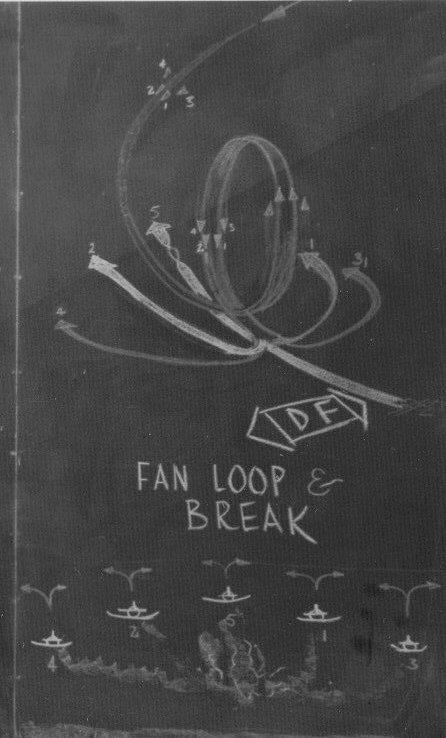

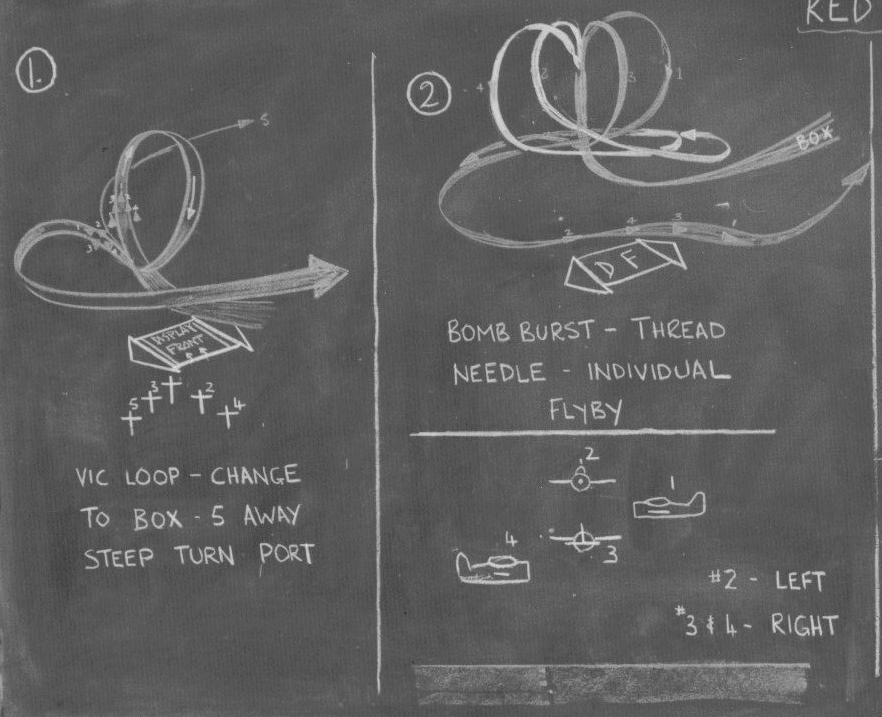

This is a very rare glimpse behind the scenes where we're privileged to see

the 1973 Red Checkers' black board showing the team routine. Below are

close-ups of the board to show detail of the routines. Ian Wright, who drew

these chalk diagrams, says , “This was my attempt to capture the

sequence of the Red Checkers routine at that time.”

1973-74 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

1974-75 Red Checkers Team ___________________________________________Harvard

Nil - see below

Flt Lt Barry Mitchell

Sqn Ldr Don McAllister

Flt Lt John Lamont

Flt Lt Peter Cochran

Flt Lt Ian Wood

Flt Lt Cecil Crook

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:The Red Checkers Harvards were scheduled to appear at the RNZAC Air Pageant, held at Tauranga Airport on the 1st of Mar 1975. Their photo was even featured on the front cover of the pageant's programme. However they did not show up, and it was left to the Minister of Civil Aviation, Dr Martyn Finlay who was present to explain to the disappointed crowd that economic reasons had seen the team's display cancelled. A No. 40 Squadron Hercules. '05, was present, and a solo display was made by Flt Lt Rod Anyan in a Skyhawk from No. 75 Squadron which closed the pageant with a 500 kt pass and vertical climb into the clouds, just before the heavens opened.

John Lamont went onto an airline career but continued his airshow display flying in the Roaring Forties Harvard team, and subsequently in various WWII fighter aircraft for the Alpine Fighter Collection and other collections. Today he's one of New Zealand's top warbirds pilots, and has been responsible for planning some of this country's best air displays, such as Warbirds Over Wanaka

Interestingly another possible attempt to reform the team came in 1976 according to Frank Sharp, who says he was sent on an...

"Instructors Course at CFS Wigram in 1976 and I was invited by Sqn Ldr Ces Crook to try-out for the reforming Harvard formatic team. I only did a couple of flights with a formation aeros sortie as No 4 of a 4 a/c formation (14/4/76). I think that permission to reform the team was withdrawn and I don't recall any Red Checkers that year."

Return of the Red Checkers

Above: Scanned from the RNZAF's Insight safety magazine from January 1981

6th of Dec 1980

28th of Feb 1981

_Wigram Wings & Wheels

Air Force Day 1981,

RNZAF Base OhakeaSqn Ldr Frank S. Sharp

Flt Lt Frank H. Parker

Flt Lt Dave J. Forrest

Sqn Ldr John S. Bates

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Reserve

Notes:Team Leader Frank Sharp tells how this team came about. After his stint at CFS mentioned above in 1976, he then went to the UK in 1977 on exchange where he learned about formation aerobatic teams from the masters:

"I was posted to UK. I was assigned Flt Lt Bobby Eccles as my instructor to convert me to the Folland Gnat. What was marvellous was that Bobby had just left the Red Arrows after three years of display flying.

We were at RAF Valley in Wales. The red Arrows were stationed at RAF Kemble in England and Bob's wife was still living there and he was commuting. Bob was still suffering withdrawal symptoms from the Arrows so, on one 'conversion' sortie, we flew to Kemble. Bob arranged for me to join the team for their display briefing then I flew in the back-seat for a full rehearsal. I then attended the debrief.

We all had lunch then I did the same again in the afternoon. Then Bob and I flew back to Valley. It was a memorable day and I learnt a lot about the team's 'modus-operandi'.

Mid 1979 I was posted back to CFS as the CO. While I had been in UK the end of the Harvard era at Wigram had occurred and the CT4B Airtrainers were in operation.

Shortly after I had converted to the CT4 I read a report written by the previous CO that stated that the CT4B was totally unsuitable for formation aerobatics. Subsequently there had been no interest in raising a team.

I couldn't help reflecting on old reports from RAF air displays at Hendon in the 1920s and 30s. Those guys did amazing things in formation in aircraft, some of which had poorer power/weight ratios than a CT4B.

With Sqn Ldr John Bates, who was the Fixed Wing Flight Commander at CFS (he was ex-Skyhawks and had recently returned from an exchange tour with the USAF flying A-10s), we set about investigating just what was or was not possible with the CT4B.

There is no doubt that, compared to its predecessor the Harvard, the CT4 had an even poorer power range that allowed for the 'outside' man to maintain station through all the conventional manoeuvres.

Harvard team; creeping forward during the early part of the vertical manoeuvre in order to compensate for the inevitable lack of power over the top.

However, we discovered just when the leader had to reduce his power and maintain his position by 'backing into the team' who would otherwise have trailed behind, particularly the No 4 in the box position.

This was nothing new as formation leaders always have to be conscious of the power requirements of others in the formation. However, with the CT4 the problem was the very narrow power range to play with as the leader started with less than full power for any manoeuvre to allow the team members to have a margin to work with.

Reducing the power further reduced the speed and hence the energy and hence the manoeuvrability. The barrel roll was probably the biggest challenge as the 'rolling while looping' needed a significant power reduction for the outside man and the number 4.

The reduction required could cause embarrassment to the inside man who had to throttle back to an uncomfortable level then had to be ready to really accelerate as we came out the bottom and went into a high wing over reversal.

We found that with a 'must have' controlled initial height and speed, careful engine husbandry by the leader and a timely call for "power" from No. 4 we could complete all of the conventional manoeuvers.

As for the mirror formation, following the adage that "nothing is new" this was also inspired by pre-war Hendon air displays. The real trick was that one CT4 had a modified oil system that allowed up to 30 seconds of inverted flight.

Once we got used to being able to maintain inverted flight for relatively lengthy periods we had the bright idea of putting the leader in the 'inverted' aircraft and have the team formate on him during manoeuvers with him inverted.

This quickly proved too difficult in addition to all the other challenges of the CT4, but, we did re-invent the mirror formation. John Bates was No. 4 and would do a solo 'fill-in' routine in front of the crowd while the rest of us clawed for more height and repositioned for the following part of the sequence.

It made sense for John to have the 'inverted' aircraft as he was able to exploit its capabilities in his solo performance. Thus, to achieve the mirror John would rejoin with me then pull a little ahead and to one -side of me and roll inverted. As soon as he was upside down I would fly underneath him and formate on him by looking up and judging distance. We could certainly hear each others aircraft and it took a bit of trial and error to work out just how to position safely as it wasn't a manoeuvre we could would really mimic on the ground.

The team consisted of Myself, No. 2 Flt Lt Frank Parker, No. 3 Flt Lt Dave Forrest, No. 4, Sqn Ldr John Bates. Frank was a helicopter instructor and a lot of this upside down stuff in formation was fairly new to him.

Dave was another ex Skyhawk pilot. It didn't occur to us to call ourselves the 'Red Checkers' although I see from the team photo that we had checker boards painted on the visor covers of our 'bone-domes'.

The team members did their jobs during the day then the team practices were invariably late in the day or in the evening to minimise the impact on the bases flight training schedule.

Like all formation teams the unsung heroes are the ground crews. The guys at Wigram were amazing at ensuring that enough aircraft were available to practise with.

Also, they literally invented the smoke system. There was not much room for an oil tank, but, with some excellent engineering they manufactured oil tanks that were unique to each aircraft (the CT4's were 'hand made' and each on varied slightly in the space available for the extra oil tank).

They then developed a 'venturi' extractor that fitted on the exhaust stubs. This allowed two smoke trails per aircraft and created very good 'smoke'. We considered colouring agents for the smoke until we discovered the cost and quickly forgot about that.

At the start we did not think it politic to seek clearance from group headquarters, but once we had convinced ourselves that e could carry out the basic manoeuvers safely we sought the necessary clearance.We were lucky that Gp Capt Colin Rudd was the base commander as he actively supported us and once we were ready to demonstrate a basic routine he had the Group Commander watch.

I don't know what transpired but we got the nod to continue but did most of our training well out of site in the training area.

Our first public display was at the Wigram "Wings and Wheels" day on 6/12/1980. The aim then became to have a Support Group team perform at Air Force Day 81 at Ohakea.

The CT4B suffered 'bad press' having replaced the venerable and much loved Harvards. It just didn't have the impact or the grunt and quickly became known as the 'plastic rat'. While I am no aplogist for the CT4B I like to think that our display at AFD 81 changed peoples attitude towards it and helped it to be accepted as the quite capable little aircraft that it was.

It was exciting proving that the CT4B could actually deliver. On one occasion the RAAF CFS had heard that we were carrying out formation aerobatics in CT4s. They also operated the CT4 but had decided that it was not capable of display standard manoeuvres. They visited us at Wigram and we put on a 'practice' display over the airfield. They insisted on making an 8mm film of the vertical parts of the sequence as they wanted to prove to their colleagues back in Oz that it was possible!"Frank Sharp went on to become CO of No. 75 Squadron, then Base Commander of Ohakea before leaving the RNZAF. Today he continues to pass on his huge depth of knowledge, helping to train pilots at a civil flying school.

Frank Parker continues today as a display pilot in the Warbirds Harvard Team, the Yak 52 team and in other display aircraft. He is currently NZ Warbirds CFI

1981-82 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer5th of Dec 1981 Wigram Wings & Wheels Sqn Ldr John Bates

Flt Lt Colin F. Pearce

Flt Lt Frank H. Parker

Flt Lt R.S. Ginders

Flt Lt R.A. JannesenRed 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

1982-83 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer4th of Dec 1982

Dec 1982

Dec 1982

Dec 1982

21-24 Jan 1983

28-29 Jan 1983

_

4-6 Mar 1983

26-27 Mar 1983

_

_4th of Apr 1983

17th of Apr 1983

28th of Apr 1983

_7th of May 1983

_'Wings And Wheels', Wigram

RNZAF Te Rapa Open Day

14 Squadron

Rotorua

Dunedin Air Show

AACA Air Pageant,

Paraparaumu AirportRNZAC Air Pageant, Hamilton

Airshow '83,

RNZAF Base Whenuapai

(RNZAF Museum Fund Raiser)Easter Races, Riccarton

RNZAF Woodbourne Airshow

Royal Display for HRH Prince

Charles, Prince of WalesSpitfire to Harvard Run,

WigramSqn Ldr Bruce Ferguson

Flt Lt Steve Bone

Flt Lt Malcolm Knox

Flt Lt Colin Pearce

Flt Lt Roger Read

Flt Lt Carl Millen

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Reserve

Note:Steve "Rover" Bone now flies Bell 412 and Augusta Westland 139 helicopters for Helicopters New Zealand Ltd. working with the oil platforms off the Taranaki coast

Des Underwood was the Engineering Officer on this team and he kindly supplied many of the details.

1983-84 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B AirtrainerLabour Day 1983

__19 Nov 1983

3 Dec 1983

7-8 Jan 1984

29 Jan 1984

Greymouth Anniversary

Air PageantTokoroa

Wigram Wings & Wheels

Tauranga

Vintage Sports Airshow, Masterton

Sqn Ldr Bruce Ferguson

Flt Lt Steve Bone

Flt Lt Roger Read

Flt Lt John McWilliam

F/Lt Paul 'Radar' O'Reilly

Flt Lt Graham Lintott

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Reserve

The 1983-84 season Red Checkers Team

A closer look at the team members: Pilots from left are Flt Lt Roger Read (Red 3 ), Flt Lt Steve "Rover" Bone (Red 2), Sqn Ldr Bruce Ferguson (Red 1, at front), Flt Lt Graham Lintott (Red 6 Reserve/Commentator, behind Bruce Ferguson), Flt Lt John "McBill" McWilliam (Red 4) and F/Lt Paul 'Radar' O'Reilly (Red 5).

The rear rank maintenace staff are, from left, F/Sgt Graham Harris, Cpl Ian Gibson, F/Sgt Warren Wintoul, F/Lt Des UnderwoodCpl Douglas Knight and Cpl Laurie Hart. Photo is Air Force Museum of New Zealand Official and kindly supplied by Doug Knight.

Note:

The team was filmed throughout this year by Television New Zealand for the excellent documentary 'The Red Checkers', which was released in 1985

1984-85 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer27th of Jan 1985

17th of Mar 1985

_28th of Apr 1985

Wigram Wings And Wheels

Airshow '85 - RNZAC

Pageant, ArdmoreRangiora Airshow

Sqn Ldr Roger Read

Flt Lt John McWilliam

Flt Lt Graham Lintott

?

?

?

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Note:Air Vice Marshall Graham Lintott is a former Chief of the Air Force

1985-86 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer8- 9 of Mar 1986

_12th of Apr 1986

RNZAC Nationals,

MastertonGisborne Airshow

Sqn Ldr Dave Forest

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:A Harvard flew with the team at the Gisborne Airshow on the 12th of April 1986 as the solo aircraft in the display, when one of the Airtrainers became unserviceable.

1986-87 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer29th of Mar 1987

1st of Apr 1987

_4th and 5th of

April 198711th and 12th of

April 1987PDL International Air Race Airshow

RNZAF 50th Anniversary

RNZAF WigramRNZAF 50th Anniversary,

RNZAF OhakeaRNZAF 50th Anniversary,

RNZAF WhenuapaiSqn Ldr Roger Read

Flt Lt Ian McClelland

Sqn Ldr A. B. MacLean

Flt Lt M. R. Wingrove

Flt J. N. Grant

Flt Lt Mark Tapp

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:Reserve pilot Flt Lt Mark Tapp flew as No. 5 and Soloist at both the RNZAF Base Whenuapai and Ohakea airshows

1987-88 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer12th of March 1988

2nd of Apr 1988

_

Airshow '88, Dairy Flat

Warbirds On Parade,

Luggate Airport, WanakaSqn Ldr Roger Read

Sqn Ldr Michael Panther

Flt Lt John Benfell

Flt Lt Mark Wingrove

Flt Lt Ian Walls

Mark Tapp

S/Ldr Hamish Brice

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Reserve

Notes:At the Wanaka event, which was the first of the now world renowned Wanaka warbirds airshows (and had been delayed over from an original date in January) the Red Checkers pilots flew the following aircraft:

NZ1943 - Sqn Ldr Roger Read

NZ1944 - Sqn Ldr Michael Panther

NZ1933 - Flt Lt John Benfell

NZ1936 - Flt Lt Murray Wingrove

NZ1934 - Flt Lt I. Walls

1988-89 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer?

Feb 1989

19 Feb 1989

_Napier

Wanganui

Wigram Wings and Wheels

(unconfirmed)S/L Mike Panther (CO)

F/L Hamish Brice

F/L Keith Adair

F/L John Benfell

S/L John Grant

F/L Glenn Edwards

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:

The Maintenance Flight Commander for the team this season was Flight Lieutenant Pete Wooding. He has kinly sent the following photos from that season.

From left to right are S/L John Grant; "Titch" Reid (ground crew); S/L Mike Panther; Terry Vulleta (ground crew); F/L John Benfell; Sgt Steve Preest; F/Lt Hamish Brice; David Crake (ground crew); F/L Keith Adair; Pete Lees (ground crew), and F/L Pete Wooding. Absent: F/L Glenn Edwards. RNZAF Official Photo

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

1990-91 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer5 Feb 1991

_16 Feb 1991

_10 Mar 1991

_3 May 1991

_

RNZAF Base Wigram for Air Race

Competitors and CrowdRNZAC Pageant,

New PlymouthWaikato Airshow '91

Hamilton AirportFlypast and Formation Aeros for

1/90 Wings Course Graduation, WigramSqn Ldr Steve Bone

Lt Hoani Hipango

Flt Lt Peter Mount

Flt Lt Brian Coulter

Flt Lt Nick "Oz" Osborne

Chris Melhopt

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Reserve

Notes:Red Checkers Engineer Team 1990-91

Flt Lt Teresa Cunningham

Sgt Philip Mackie

Sgt Steven O'Shaughnessy

Cpl Sean Tucker

AC Kimbal HughEngineering Officer Teresa Cunningham was the first female member of the Red Checkers team

Four out of the five members in the display team were helicopter pilots, the first time so many who specialised in that field had dominated the team

The team only performed four shows this season, according to the Waikato Times dated 9th of March 1991, with Hamilton being their final show for the summer. The article quotes Steve Bone as saying the team had formed in August 1990 in preparation for their first show in November 1990

Steve Bone recalls that the Waikato Airshow '91 at Hamilton was raising funds for the Crippled Children's Society

Above: The Red Checkers Team at the Waikato Airshow '91, Hamilton Airport. Photos - Dave Homewood

1991-92 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer9 Feb 1992

_18 Feb 1992

1 March 1992

7 March 1992

28-29 Mar 1992

_17-19 Apr 1992

(Easter)20-22 of Nov 1992

??

_

_

South Otago Aero Club

60th Anniv. Airshow, BalcluthaDunedin Festival

Whenuapai Wings & Wheels

Wigram Wings & Wheels

RNZAC Pageant, Nelson

(two performances)Warbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateAir Expo 92, Mangere

Over Lancaster Park,

Christchurch

during NZ Cricket GameSqn Ldr Ian McLelland

Sqn Ldr Hoani Hipango

Flt Lt Nick 'Oz' Osborne

Flt Lt Phil Murray

Flt Lt Mike Tomoana

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5 (s)

Reserve

Notes:Red Checkers Engineer Team 1990-91

Flt Lt Teresa Cunningham

Sgt Trevor Wood

Sgt Philip Mackie

Cpl Glenn Hughes

LAC Doug Hilliard

AC Blair Hopkins- Ian McLelland was Commanding Officer of CFS, and had been involved previously in Peacekeeping in the Middle East

- The No. 2 position was intended to be filled by Sqn Ldr Glen Edwards but at the last minute he was posted away from Wigram and he was relaced in the team by Hoani Hipango, who was formerly a Royal New Zealand Navy pilot before transferring to the RNZAF and had served as No. 2 in the team the previous year

- Nick Osbourne was previously well known as a Skyhawk pilot with the Kiwi Red team

- Phil Murray had previously been an agricultural pilot, and then joined the RNZAF. He was a helicopter instructor during this time. He was also well known for other airshow acts such as his 'crazy flying' routine in a Piper Cub, and as a warbirds pilot flying Sir Time Wallis's P-40K Kittyhawk

- Mike Tomoana had previously flown Lockheed P-3K Orions with No. 5 Squadron from 1985-88 and then Cessna 421C Golden Eagles with Woodbourne-based No. 104 Flight for the next two years. On becoming an instructor, Mike served through 1990 with the Central Flying School, and then moved to the Pilot Training Squadron where he instructed through 1991-92. He then returned to flying Orions till 1995, when he left the RNZAF to fly for Air New Zealand.

- Pete Cochran was the Commanding Officer of the RNZAF Historic Flight, and the Red Checkers team's regular commentator and reserve pilot for this season.

- At the Balclutha airshow the regular team commentator Pete Cochran was unavailable so Flt Lt Jim Finlayson stood in.

- At the Air Expo 92 airshow, the five aircraft used in the display were NZ1931, NZ1932, NZ1938, NZ1940 and NZ1944)

- Some good footage of the 1992 Red Checkers team performing appears in the official video of the Air Expo 92 airshow held at Auckland International Airport, Mangere, Auckland. As well as footage it includes radio calls from Ian McLelland. The video was released in 1993 by Endeavour Entertainment

- The team this season had three pilots of the five of Maori descent, and they affectionately called themselves jokingly 'The Brown Checkers'.

1992-93 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer20 Jan 1993

March 1993

_Waikato Aero Club 60th, Hamilton

Wigram Wings and Wheels

ChristchurchSqn Ldr Ian McLelland

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Flt Lt Phil Murray

Flt Lt Bruce Craies

Flt Lt Paul Hughan

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Notes:- I'm uncertain the team positions for this year's team. The info above is based purely of the video 'Wings and Wheels: The Final Wings And Wheels At Wigram" (1993, RNZAF Museum) which lists the team in this order - Ian McLelland was certainly No. 1

- In December 1992 at the RNZAF Base Wigram 'Village Green' Day (which is a special annual sports day and Christmas party held on all the bases) this Red Checkers team performed a stunning routine of aerobatics for the whole base - on their bicycles! They wore their flying overalls and helmets with the Red Checkers markings, and rode in formation performing several 'stunts', much to the delight of the crowd who enjoyed this with great humour.

1993-94 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer24 Oct 1993

_30 Jan 1994

19 Feb 1994

_25-26 Feb 1994

27 Feb 1994

13 Mar 1994

20 Mar 1994

1-3 Apr 1994

(Easter)Stratford Aero Club/ATC

Anniversary Air ShowNZ Grand Prix, Manfield

RNZAC/AACA Air Expo,

ParaparaumuWanganui Festival

Wigram Wings and Wheels

Ohakea Wheels

Whenuapai Wings and Wheels

Warbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateSqn Ldr Ian McClelland

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

Flt Lt Phil Murray

Sqn Ldr Phil Wilson

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Note:

One of the members of the ground maintenance staff was Sgt Barry Moore

1994-95 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer4th of Dec 1994

_20th of Dec 1994

6-7 Jan 1995

_4-5 Feb 1995

17th of Feb 1995

17th of Feb 1995

_

_18th of Feb 1995

19th of Feb 1995

3rd of Mar 1995

14-16 Apr 1995

_

(Easter)Exercise Wise Owl 63,

Tauranga AirportPatea

World Gliding Champs,

OmaramaParaparaumu Airshow

RNZAF Woodbourne

Meadow Fresh Children's

Fiesta Day, Hagley Park

ChristchurchRangiora

Wigram Wings and Wheels

RNZAC/AACA Airshow,

Warbirds Fighter Meet,

Waipukarau

Hamilton AirportSqn Ldr Ron Thacker

Sqn Ldr Phil Wilson

Flt Lt Shane Harrison

Sqn Ldr Peter Cochran

Sqn Ldr Jim Rankin

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Official Team Photo - left to right are Sqn Ldr Peter Cochran (Red 4), Sqn Ldr Phil Wilson (Red 2), Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker (Red 1), Flt Lt Shane Harrison (Red 3) and Sqn Ldr Jim Rankin (Red 5). RNZAF Official Photo kindly supplied by Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

Note:

One of the members of the ground maintenance staff was Sgt Barry Moore

1995-96 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer19th of Jan 1996

20-21 Jan 1996

10th of Feb 1996

24th of Feb 1996

9th of Mar 1996

10th of Mar 1996

19th of Mar 1996

_21st of Mar 1996

_4-8 Apr 1996

(Easter)5th of April 1996

Ohakea Open Day

SVAS Airshow, Masterton

SAA Expo, Matamata

Whenuapai Wings and Wheels

Auckland Harbour Skyshow 96

Ohakea Wings and Wheels

Wanganui International

Police GamesRNZAF Base Woodbourne

GSTS Graduation ParadeWarbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateDunedin Harbour

Sqn Ldr Graham Cheal

Sqn Ldr Pete Doole

Flt Lt Damien Gilchrist

Sqn Ldr Peter Cochran

Sqn Ldr Murray Neilson

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Notes:

Sadly, Sqn Ldr Murray Neilson was later killed while practising for an aerobatic display whilst commanding No. 2 Squadron (Skyhawks) at Nowra, Australia

This was the final Red Checkers team to fly in the International Orange and Dove Grey colour scheme (ie: Red and Grey as seen in the photos). The CT/4B's were subsequently repainted in the yelow and black scheme of today.

The following photographs show the 1995-1996 season:

Above: The Team - the pilots in the front row are - left to right - Pete Cochran, Damien Gilchrist, Graham Cheal, Pete Doole, Murray Neilson.

The back row are members of the ground maintenace staff staff are, left to right, are believed to be LAC Corey Price, Sergeant Barry Moore (Aircraft Technician), Flying Officer Greg Poole (Engineering Officer), Corporal Lynne Hill (Safety and Surface Technician) and LAC Chris "Fetus" Bevan. Though the three inner ground staff are confirmed as correct, if you can confirm or correct the two outer ground crew names please contact me (RNZAF Official)

Another formal team shot, this time with the pilots to the rear, and the groundcrew to the foreground. Lef to right front row, believed to be LAC Corey Price, Sgt Barry Moore, Flying Officer Greg Poole, Corporal Lynne Hill and LAC Chris Bevan. Back row, left to right, Pete Cochran, Damien Gilchrist, Graham Cheal, Pete Doole, and Murray Neilson. NZ1940 is seen to the left of the background. (RNZAF Official, supplied by Barry Moore)

The team at Wanaka for the Easter airshow. Left to right, standing, are Lynne Hill, Pete Cochran, Graham Cheal, Barry Moore, Cpl Murray Wyatt, Murray Neilson on wing, Greg Poole and Damien Gilchrist. Kneeling in front, Sgt 'Skip' Ward, Chris Bevan and Coey Price. The Airtrainer is NZ1946 (RNZAF Official, supplied by Barry Moore)

A loop over Queenstown.

Above: The Mirror Formation. Graham Cheal says:

"As leader, I did the inverted part of the mirror so it was important I got to know exactly how long that particular aircraft would run inverted before running out of gas - around 40 secs (some were only 25 secs). For this reason we normally tried to keep the leaders aircraft the same for all displays. I would pull ahead and roll inverted and #4 (Pete Cochran) flew in underneath. In this shot he is actually moving forward into position. Normally the tails are inline with a minimum of 4 feet between the tail tips. When in position, Pete would have his head hard back, as far as he could, but he could only really see from the nosewheel forward. Pete couldn’t wear a Mae West (lifejacket) as it restricted his head movement so he could only see the propeller spinner. The worst aspect of this manoeuvre was, the possibility of an engine failure for me inverted at 500 feet, with another aircraft underneath me. After an engine failure, I had to hold it inverted, with speed decaying until #4 got out of the way. Once clear, I would slow roll out with very little airspeed left and accept the terrain in front of me, for a forced landing. We practiced this manoeuvre regularly to ensure the safety of the crowd."

Above: The Heart Break. Graham Cheal says:

"In this photo, I have just called ‘Heartbreak …Go” and #2 and 3 roll 90 degrees outward, and myself and #4 continue up for a few seconds. #4 slips back an aircrafts length and sits a little deeper (to avoid my wash), and after a few seconds I call “pull” and we both simultaneously pull over the top and change the lead, and I slot into line astern behind # 4, and we pull out moving to line abreast as we come through the middle of the heart made by #2 and 3."

Above: The Box Formation Loop. Graham Cheal says:

"Note the position of #4 (aircraft 33). As we dive down for the loop, #4 goes to full power and ends up almost directly underneath me when I pull up for the loop. He maintains full power, but as he has to fly a bigger circle than the others, he slowly drifts back (despite full power), so by the time of the exit of the loop he has drifted back to the normal line astern position. A nifty bit of flying and very hard to tell from the ground, but this photo shows quite clearly, he is well forward of his normal position. In more powerful aircraft, this technique is not required as they can just add lots more power to hold the normal line astern position."

Red Checkers team members and other Pilot Training Squadron staff celebrate as the Airtrainer fleet's 50,000th hour of service ticks over. From left, Barry Moore, Shaun Clark, AC Bucan, Brian Caruthers, Wing Commander Ian 'Iggy' Wood, Greg Poole, Tim Sherbourne, Chris Bevan. Kneeling in front: Mike French, Bryce Rodgers, Corey Price

1996-97 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer19th of Jan 1997

_27th of Jan 1997

27th of Jan 1997

8th of Feb 1997

15th of Feb 1997

21st of Feb 1997

21st of Feb 1997

22nd of Feb 1997

22th of Feb 1997

28th of Feb 1997

15th of Mar 1997

16th of Mar 1997

SVAS, Hood Aerodrome,

MastertonAuckland Regatta Flypast

North Shore

Hamilton Flypast

Wellington Flypast

RNZAF Base Woodbourne

Christchurch Flypast

Nelson Flypast

Westport

Auckland Flypast

Gisborne

Napier

Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

Sqn Ldr Steve Alderton

Sqn Ldr Pete Doole

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Sqn Ldr Cameron Smith

Sqn Ldr Andrew "H" Greaves

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:

Sqn Ldr Steve Alderton is better known in the RNZAF as "Rah"

Sqn Ldr Andrew Greaves, also known as "H", was the commentator and spare pilot for this season

The Airtrainers for this season wore a special emblem on their tails marking the 60th Anniversary of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Here is the emblem, as worn on former NZ1935 (now ZK-JMV) which is based at the Classic Flyers Museum at Tauranga (photo taken February 2010)

The following photo shows the 1996/97 team

Back Row: Maintenance staff, left to right, Corporal "Gov" ?? (Aircraft Technician), AC Wayne Cook (Aircraft Mechanic), Sergeant Murray "Muzz" Wyatt (Aircraft Technician), Flight Lieutenant Charlie Morris (Mainteance Flight Commander), Sergeant Don Simms (Avionics Technician), LAC Brent Woodly (Aircraft Technician).

Front Row: Pilots, left to right, Squadron Leaders Pete Cochran, Steve "Rah" Alderton, "H" Greaves (at rear), Ron Thacker (in front), Pete Doole, Cameron Smith.

1997-98 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4B Airtrainer18th of Dec 1997

18th of Jan 1998

7th of Feb 1998

8th of Feb 1998

28 Feb-1 Mar 1998

19th of Mar 1998

22nd of Mar 1998

31st of Mar 1998

10th of Apr 1998

11-12 Apr 1998

(Easter)10th of June 1998

Ohakea Flypast

Masterton

Matamata

Tauranga

Whenuapai

Woodbourne

Ohakea

New Plymouth

Dunedin

Warbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateHamilton Flypast

Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

S/L Andrew "H" Greaves

Sqn Ldr Peter Doole

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Ian Saville

Tim Styles

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Official Team Photo - left to right are Sqn Ldr Peter Cochran (Red 4), Sqn Ldr Andrew Greaves (Red 2), Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker (Red 1, at front), Tim Styles (Reserve/Commentator, behing Ron Thacker), Sqn Ldr Peter Doole (Red 3) and Ian Saville (Red 5).

The names of the five maintenance staff at rear are still needed. RNZAF Official Photo kindly supplied by Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

1998-99 Red Checkers Team ____________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer24th of Jan 1999

20th of Feb 1999

_26th of Feb 1999

28th of Feb 1999

18th of Mar 1999

Masterton

13th World Precision Flying

Championships, HamiltonWigram Flypast

Westport

RNZAF Base Woodbourne

Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

Goodwin

Ian Saville

Sqn Ldr Pete Doole

Sqn Ldr Andrew "H" Greaves

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

George Evans

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

Reserve

Official Team Photo - left to right are Sqn Ldr Peter Doole (Red 4), Goodwin (Red 2), Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker (Red 1, at front), Sqn Ldr Peter Cochran (Red 6, behing Ron Thacker), Ian Saville (Red 3) and Sqn Ldr Andrew "H" Greaves (Red 5). George Evans (Red 7, the spare pilot and commentator, is in the back row in the 'zoombag' flight suit.

The names of the five maintenance staff at rear are still needed. RNZAF Official Photo kindly supplied by Sqn Ldr Ron Thacker

Notes:

This team had six aircraft in the actual display team, with a seventh aircraft as spare flown by George Evans, who was also the commentator

This was the first Red Checkers team to use the new Pacific Aerospace Industries CT-4E Airtrainers

11 -13 Feb 2000

21-23 Apr 2000

_

Sport Avex, Matamata

Warbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateS/Ldr Andrew "H" Greaves

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

Reserve

2000-01 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer13-15 Apr 2001

(Easter)Classic Fighters Airshow,

Omaka, BlenheimRed 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

Reserve

2001-02 Red Checkers Team _____________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer29-31 Mar 2002

(Easter)Warbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateSqn Ldr Jim Rankin

Flt Lt Mark Casey

Flt Lt Sarah Hodges

Sqn Ldr Peter Cochran

Sqn Ldr Wal Thmpson

Flt Lt Andy Greig

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:Flt LT Sarah Hodges (who later became Sqn Ldr Sarah Curry) was the first female pilot to fly with the Red Checkers team

2002-03 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E AirtrainerJan 2003

19th of Jan 2003

_

_8-9 of Mar 2003

18-20 Apr 2003

(Easter)Twizel Airshow

Round 2 NZ Inflatable

Boat Championships,

Himatangi BeachArdmore Airshow

Classic Fighters Airshow,

Omaka, BlenheimRed 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

NoteOne of the CT/4E's seen at the Ardmore Airshow was NZ1995

2003-04 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer4th of Mar 2004

9-11 of Apr 2004

(Easter)Over Wellington (see here)

Warbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateRed 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

Reserve

2004-05 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer22nd of Jan 2005

_

25-27 Mar 2005

(Easter)9th of April 2005

Wings Over Wairarapa, Hood Aerodrome, Masterton

Classic Fighters Airshow,

Omaka, BlenheimRNZAF Station Whenuapai

Sqn Ldr Ian McPherson

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Flt Lt Scott McKenzie

Sqn Ldr Sean Perrett

Sqn Ldr Ian "Sav" Saville

Flt Lt Al Hay

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

2005-06 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer_3rd Sept 2005

__

_

25-26 Mar 2006

__

14-16 Apr 2006

(Easter)_Flypast at Paraparaumu

Aviation Museum's Open Day

and VJ CommemorationsRNZAF Museum Wigram

Open DaysWarbirds Over Wanaka

Airshow, LuggateSqn Ldr Mark Casey

Flt Lt Ken Spiers

Flt Lt Nick Cree

Flt Lt Aussie Smith

Flt Lt Brent Smith

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Note:CT/4E Aircraft used by the Red Checkers display team at the Warbirds Over Wanaka airshow in April 2006 were NZ1985, NZ1990, NZ1991, NZ1992 and NZ1993.

2006-07 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer12th Nov 2006

_

20-22 Jan 2007

_21st Jan 2007

22nd Jan 2007

_27th Jan 2007

_27th Jan 2007_

28th Jan 2007

_8th Feb 2007

10-11 Feb 2007

_11th Feb 2007

_

10-18 Feb 2007

_16-18 Feb 2007

3rd Mar 2007

_9th Mar 2007

_10th Mar 2007

_10th Mar 2007

18th Mar 2007

_24th Mar 2007

31st Mar 2007

_

6-8 Apr 2007

20-22 Apr 2007

Flypast for Armistice in

Cambridge, at 11.11hrs

Wings over Wairarapa

MastertonExercise Skytrain, Napier

Walsh Memorial Trophy

MatamataStratford Aero Club

70th AnniversaryLittle Day In, Waiheke Island

Auckland Match Racing

Cup Auckland HarbourOtago Boys High School

Cost to Coast Finish,

Sumner, ChristchurchWigram Warriors - RNZAF

Museum Open Day, WigramNZ Masters Games,

WanganuiArt Deco Festival Napier

RNZAF 70th Anniversary

Open Day, WhenuapaiWild Food Festival

HokitikaTrolley Derby

Collingwood, NelsonMotueka Airshow

NZ Surf Lifesaving

Champs , GisborneHalcombe School Gala

Maadi Cup, Lake

Karapiro (four-ship only)Classic Fighters, Omaka

V8 Supercars Pukekohe

Sqn Ldr Steve Hunt

Flt Lt Craig Mason

Flt Lt Al Hay

Sqn Ldr Mark Casey

Flt Lt Oliver Bint

Sqn Ldr Kennedy Speirs

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:

Thanks to Squadron Leader Glenn Davis of the RNZAF for information on the 2006/2007 team displaysThe commentator for this year's team was Flight Lieutenant Kate Clark, and the team's administrator was Flying Officer Trish O'Neill. In addition, the contractor Aeromotive (who lease the CT-4E's to the RNZAF) provided two maintenance staff members to the team when on deployments.

Two media stories from this season's Red Checkers can be read here

2007-08 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer20th Jan 2008

9th Feb 2008

_10th Feb 2008

-15-16 Feb 2008

17th Feb 2008

24th Feb 2008

2nd Mar 2008

March 2008

-16th Mar 2008

22-24 Mar 2008

16-17 Mar 2008

5th Apr 2008

6th Apr 2008

Taupo A1GP Race

Coast to Coast Race Finish

Line, ChristchurchRNZAF Museum

Open Day, WigramArt Deco Festival, Napier

Sport Avex, Tauranga

Taieri Airshow, Dunedin

Levels, Timaru (Wise Owl)

Exercise Skytrain,

RNZAF WoodbourneRNZAF Open Day, Ohakea

Warbirds Over Wanaka

V8 Supercars at Hamilton

Maadi Cup, Lake Ruataniwha

Timaru Super trucks meeting

Sqn Ldr Shaun Clark

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Sqn Ldr Paul Stockley

Sqn Ldr Scott McKenzie

Flt Lt Dwight Weston

Flt Lt Charles Weston

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:The support crew for this season were Warrant Officer Ty Cochran as commentator and airshow organiser, and Flight Lieutenant Michelle Christie as administrator for the team.

2008-09 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E AirtrainerJan 2009

_15-16 Jan 2009

_25th Jan 2009

8 Feb 2009

21st Mar 2009

10-12 Apr 2009

Walsh Flying School,

MatamataWings Over Wairarapa,

MasteronTaupo A1GP

Wigram, Christchurch

Whenuapai Open Day

Classic Fighters, Omaka

Sqn Ldr Scott McKenzie

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Flt Lt Donovan Burns

Sqn Ldr Dan O'Reilly

Flt Lt Charlie Beetham

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Reserve

Notes:The team commentator for this season is Flight Lieutenant Ty Cochran, with Pilot Officer Neil Chappell as administrator for the team. Further team notes are on the RNZAF Website here:

During the A1GP display at Taupo the Red Checkers aircraft landed on the main straight of the track, and did some doughnuts before taking off again. Superb!

During the Classic Fighters Airshow at Omaka leader Scott McKenzie did some of the commentating for the team from the cockpit.

During the Classic Fighters Airshow at Omaka the team performed perhaps their most remarkable and spectular display ever, with lights on in the twilight as the sun was setting. The pilots maintained their extremely close formation despite the poor light - which was dark blue in the east and pink in the west - and the whole normal routine was flown with great skill.

_

2009-10 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer28 Nov 2009

6 Dec 2009

_6 Dec 2009

_Lake Taupo Cycle Challenge

Pearl Harbor Open Day,

NZ Warbirds, ArdmoreBrowns Bay Christmas

FestivalSqn Ldr Scott McKenzie

Sqn Ldr Nick Cree

Flt Lt Campbell Harvey

Flt Lt Hayden Sheard

Flt Lt Jeremy Church

Flt Lt Mike Williams

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

Notes:

The Red Checkers sadly suffered their first ever fatal accident on the morning of the 14th of January 2010, during a routine practice over the Raumai Weapons Range at Sandtoft, near to Ohakea. Squadron Leader Nick Cree, aged 32, lost his life. RIP

The team was scheduled to fly the following displays but due to the accident they were cancelled (as it stands now in January 2010, this may change):

Bruce McLaren Festival of Speed, Hampton Downs (23 - 24 Jan 2010)

Speights Coast to Coast (13 Feb 2010)

Art Deco Festival, Napier (19 - 21 Feb 2010)

Wild Food Festival, Hokitika (13 Mar 2010)

Warbirds Over Wanaka (2 - 4 Apr 2010)

2010-11 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer30th of Jan 2011

30th of Jan 2011

30th of Jan 2011

13th of Feb 2011

_

_13th of Feb 2011

20th of Feb 2011

of Mar 2011

9th of April 2011

15th of Oct 2011

_16th of Oct 2011

_Hampton Downs, Meremere

Auckland

Hamilton

Speights Coast to Coast

Finish Line Flypast, ChristchurchHelicopter Heroes, Wigram

Art Deco Weekend, Napier

Wings Over Wairarapa

Dargaville

Queens Wharf, Auckland for Rugby World Cup 2011

Queens Wharf, Auckland for Rugby World Cup 2011

Sqn Ldr Jim Rankin

Flt Lt Matt Alcock

Sqn Ldr Baz Nicholson

Flt Lt Graham Burnnand

Sqn Ldr Anthony Budd

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Above: The 2010/11 Red Checkers Team, left to right, Flt Lt Graham Burnnand,

Flt Lt Matt Alcock, Sqn Ldr Jim Rankin, Sqn Ldr Baz Nicholson and

Sqn Ldr Anthony BuddNotes:

This team was scheduled to appear at Classic Fighters Airshow at Omaka, Marlborough, but they were forced to withdraw due to illness with a team member

2011-12 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer25th of Mar 2012

25th of Mar 2012

26th of Mar 2012

27th of Mar 2012

27th of Mar 2012

28th of Mar 2012

31st of Mar 2012

_2nd of Apr 2012

2nd of Apr 2012

3rd of Apr 2012

4th of Apr 2012

6-9 Apr 2012

Auckland Waterfront

Tauranga

Rotorua Waterfront

Gisborne Waterfront

Taupo Waterfront

New Plymouth

RNZAF 75th Anniversary Airshow, RNZAF Base Ohakea

Wellington City Waterfront

Kaikoura

Timaru

Dunedin

Warbirds Over Wanaka

Sqn Ldr Oliver 'Binty' Bint

Sqn Ldr Matt Alcock

Sqn Ldr Barry Nicholson

Sqn Ldr Pete Cochran

Lt Cdr Wayne Theobold

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Notes:

The year 2012 marked the Royal ew Zealand Air Force's 75th Anniversary as a seperate air arm. To celebrate the RNZAF Red Checkers did a tour of displays over cities and towns

This was Squadron Leader Pete Cochran's final season with the Red Checkers team, following a long career with the RNZAF that began in 1966, and having displayed in 19 different Red Checkers teams since 1975

2012-13 Red Checkers Team __________________________________CT/4E Airtrainer26-27 Jan 2013

27 Jan 2013

28 Jan 2013

28 Jan 2013

6 Feb 2013

8 Feb 2013

9 Feb 2013

10 Feb 2013

15-17 Feb 2013

2-3 March 2013

5 March 2013

5 March 2013

6 March 2013

7 March 2013

7 March 2013

9 March 2013

23 March 2013

29-31 Mar 2013

6-7 April 2013

9 April 2013

9 April 2013

10 April 2013

10 April 2013

11 April 2013

13-14 Apr 2013

Hampton Downs Motor Racing Track

V4 Drag Racing, Meremere

Mission Bay, Auckland Waterfront

NZ International Airshow, North Shore

Waitangi, Northland (Waitangi Day)

RNZAF Base Woodbourne

Coast to Coast Race Finish, Sumner

Tahunanui Beach, Nelson

Napier Art Deco Weekend

NZ PGA Tournament, Queenstown

Te Anau

Invercargill

Oamaru

Wanaka

Tekapo

Hokitika Wild Foods Festival

Maadi Cup, Lake Karapiro, Cambridge

Classic Fighters Airshow, Omaka

Balloons Over Waikato, Hamilton

Rotorua

Tauranga

Whangamata

Whitianga

Whangarei

V8 Supercars, Pukekohe

Sqn Ldr Oliver 'Binty' Bint

Flt Lt Stuart Anderson

Flt Lt Mick Walls

Sqn Ldr Matt Alcock

Flt Lt Jimmy Davidson

Flt Lt Robert Cato

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

Notes:

The Red Checkers Display Director this season was Warrant Officer Ash Wilson

Aircraft Allocated to the pilots this season are:

Sqn Ldr Oliver Bint

Flt Lt Stuart Anderson

Flt Lt Mick Walls

Sqn Ldr Matt Alcock

Flt Lt Jimmy Davidson

Flt Lt Robert Cato

Red 1

Red 2

Red 3

Red 4

Red 5

Red 6

NZ1993

NZ1992

NZ1989

NZ1999

NZ1987

NZ1986 (Spare Aircraft)

However during Classic Fighters 2013 at Easter F/Lt Stu Anderson was flying NZ1986 with his name on the side, and S/Ldr Matt Alcock flew NZ1988 with his name on the side too. And in the final display of the massed formation pass at this show the leader, S/Ldr Oliver Bint, was flying NZ1991, probably the spare aircraft, whilst in earlier displays at the show he was in the 75th Anniversary marked NZ1993 as usual.

End of an Era

At the end of 2013 the Airtrainers were suffering from structural issues in their wings and the fleet was grounded for a period, with some of the aircraft returning to service after major checks. However by January 2014 it had been decided that there would not be a 2014 Red Checkers team. And in that month the Government signed a deal with Beechcraft to purchase Texan II turboprop advanced trainers to replace the Airtrainer fleet. As the Texans began to arrive in New Zealand in mid and late 2014 it was announced that Pilot Training School would be disbanded and replaced by the reformation of No. 14 Squadron RNZAF, to which the new Texans would be assigned. As a result of the new squadron, and despite the fact CFS would also continue to exist and use the new Texans, it was decided to retire the Red Checkers team name for good. A competition opened to name the new No. 14 Squadron display team, which would open its first season in 2016.

After 47 years of sterling service to the RNZAF in showing the public the skills of our Air Force pilots, the Red Checkers who'd flown Harvards, CT/4B Airtrainers and CT-4E Airtrainers, were no more. The CT-4E's left RNZAF service in December 2014.

.jpg)

a.jpg)

b.jpg)

a.jpg)

b.jpg)

a.jpg)

b.jpg)