Eric FORD

Service Number: NZ401057

RNZAF Trade: Engine Mechanic

Original RNZAF Service: 4th of May 1938 till the 15th of September 1938

Date of Enlistment: 19th of April 1940

Date of Demob: 17th of December 1945

Served on HMNZS Achilles: 25th of March 1941 till 13th of June 1942

Rank Achieved: Sergeant

Flying Hours: unknown (as passenger/engineer)

Operational Sorties: nil

Date of Birth: 15th of August 1915, at Pleasant Point, Timaru

Date of Death: 3rd of October 2008, at Resthaven, CambridgeEric's Story

Eric Ford was one of the few men who served in the Royal New Zealand Air Force before the war broke out. He joined up and was attested at Trentham on the 4th of May 1938. He was posted to RNZAF Station Hobsonville and he was present when the RNZAF's first Airspeed Oxfords arrived by sea at Hobsonville wharf in July 1938. He was one of the team members who assembled the RNZAF's five prewar Oxfords for service. Eric decided however to leave the RNZAF, and was discharged from Hobsonville on the 15th of September 1938.

As soon as the war broke out, duty called and Eric volunteered for service in the RNZAF again, with the initial desire of becoming a pilot.

However, his plans were stymied because of his previous profession. He explained to me when I interviewed him on the 28th of August 2003,, “No way would you be allowed to be a pilot, not if you had any mechanical background. They were very short of mechanics.”

Because he was already an A Grade mechanic by trade, Eric was forced instead to become an engine mechanic. He recalls the early days when he first entered the Air Force.

“Well, they weren't really ready for us. I was at Timaru, and they called us in, and they shoved us off down to Dunedin. There was nothing down there, but we had an old Baffin, in amongst the residents. No wings on it, just the motor sitting in the front. And we used to start this thing up in the town and just about blow it to pieces!”

“It was out in the back yard. It was railway property, it was just part of the railway workshops, and these tutors were imported Poms. And they knew their drill all right.”

“I was at Hobsonville for a while. I was at Hobsonville when the first Airspeed Oxford arrived. Anyway, we went to Wigram, and they were training these pilots. They were poking them through by the hundreds, in these old Baffins it was. And they used to go out with an instructor, and fly back, and you'd say ‘go on out for yourself'. If they came back, they'd give ‘em three stripes and a set of wings, and say ‘You're a pilot.'

“And they shipped them to England, and I don't think too many of them survived.”

At RNZAF Station Wigram, Eric was servicing the engines on the Blackburn Baffins.

“You got very sick of it, you know, it was just one after the other. You had to keep them in the air. The old Peggy motors in them.”

It was at Wigram that Eric chose to take a new career path, when he applied to go on board a Royal New Zealand Navy ship. He wrote the following memories as a submission for the book The Golden Age of New Zealand Flying Boats by Paul Harrison (Random House, Auckland, 1997). The book only used extracts from it, it is published with Eric's permission here in full.

An Airman Joins The Navy

“About the middle of March 1941 a notice appeared on the notice board at Wigram Air Force Station requesting an aero engine mechanic to service Walrus Seaplane on the H.M.N.Z.S. Achilles. I volunteered, like many others, hoping this was a means of getting overseas. Luckily I got the posting.

Talk about being dropped in at the deep end. I reported to the ship some time in early April at Devonport Naval Base. There I was handed a hammock and told, “That's for sleeping in.” I had no idea what to do with the thing, but there were plenty of willing hands who tied the thing up to the ceiling, and I was told I had eighteen inches to sleep in. The biggest problem was how to get into it without going out the other side. Upon mastering the art of retiring, I found it most comfortable to sleep in.

It was customary, as a fire protection, to drain the fuel from the aircraft each night after sunset and return it each morning before daylight. This was to protect the torpedo tubes, which were placed right under the catapult, from possible fire in case of action at night. The torpedoes were considered front line defence after dark.

The first morning out we were sailing for Wellington – weather a bit rough. Groping along the ship's waist in the dark – no lights – to refuel the aircraft (Pusser Duck). I stepped over a steel baffle which was there to stop the sea in rough weather from going below decks, and stepped into about six inches of water! What a shock I got – I thought I had stepped overboard!

The draining and refueling was not popular with the crew as, while this fueling was going on, nobody was allowed to smoke on deck. It was my duty to fuel the aircraft and each morning I would don a safety belt and climb up on top of the mainplane (wing) where the two fuel tanks were situated, one on each side, and hook the safety belt onto the hasp provided. It was a long way up off the deck and pretty scary when the ship was rolling.

The rigger (a member of the crew) whose duty it was to sit in the cockpit and watch the fuel gauges, and inform me when they were getting full, would occasionally drop off to sleep, and the first thing I would know when the tank was full was when I was afloat in petrol. Never mind, we mechanics had the last say when it came to start up the engine. It was the rigger's job to wind the inertia starter (which was quite hard work). When he got it up to speed he would call, “Contact!” to me sitting in the cockpit, and I would switch on and with a little bit of luck the engine would burst into action, but if your petrol-sodden trousers were still uncomfortable one was in no hurry to switch on, and the whole procedure would have to be repeated. By this time he would be gasping for breath, and hoping he had not fallen asleep earlier.

What a dangerous job it was to recover the aircraft under sail in rough weather. The procedure was for the ship to turn sharply, causing flat-water slick, which the aircraft would land in, and then power alongside the ship. The crane would be luffed out ready to lift on board. This is where the excitement would come in, with quite a large gallery watching (sailors off duty).

The procedure was for the crane driver (who had to be a wizard at the controls), to drop a light cable down to the person on top of the wing ready to hook on to a sling. Once hooked a much heavier cable would slide down the lighter cable and automatically grab the sling. Think of the poor soul trying to hook up, with the aircraft bobbing up and down, and hoping that the attached safety belt would take charge and not allow his feet to get tangled with the still-running propeller. Once safely out of the water the next job was to try and catch the aircraft as it is swung backwards and forwards over the catapult. Imagine the ship rolling (as it always seemed to do) and the aircraft dangling on the end of the crane. Once caught, six small block-and-tackles would be attached criss-cross to steady it onto the cradle on the catapult.

Procedure to catapult the aircraft off at sea could be another tricky time. The aircraft would be positioned to the rear end of the catapult, which is fully extended being in three sections. With the engine running at full revolutions awaiting the firing of 7lb of cordite, which would give it its initial thrust, hoping it would have sufficient speed to be airborne on leaving the ship.

We had a transfer of pilots, and the only conversion the new guy got to the Duck was a push off the catapult with current pilot and me while the ship was tied up at Devonport wharf. I was there to hook up on return. All went off OK – a credit to a 20-year-old pilot (Johnny McGrane).

The Walrus was a pusher type amphibian craft powered by a Pegasus radial engine. It carried a crew of three – Pilot, Navigator and Radio Operator. It had a Lewis gun mounted in the forward hatch, and was capable of carrying two 100lb bombs. It had a cruising speed of 120mph with about a five hour range and supposed to be capable of landing in a 7ft swell – a very versatile and reliable machine, such as sneaking ill-gotten gains ashore (grog and cigarettes) dodging Customs, delivering the mail, and even fishing.

It was surprising how everyone worked in with each other, especially if one was to offer a drink of one's rum (called sippers). Whilst tied up at Devonport I was asked to fill up a 44-gallon drum with petrol – no names mentioned, no questions asked. The crane driver loaded it on to a P&T truck who did all the Navy's transport by just a phone call. I believe it was kicked off the truck out in the country somewhere. All official, and someone had extra transport, with 100 octane petrol. Petrol was in short supply and difficult to come by.

The crew to operate and service the aircraft was quite considerable, consisting of Pilot (Air Force), Navigator and Radio Operator (Navy). Service crew were Rigger Airframe, Engine Mechanic, Radio Mechanic, Armourer and Writer who kept all our records. These were all Air Force personnel. The parachute packer was a naval rating trained in this art. This was necessary as the chutes had to be hung in a drying cupboard from time to time. A chute will not open readily if it is damp. All flying crew carried a chute.

Leander and Achilles were anchored in or around Noumea and we were doing early morning patrol with our aircraft, and it was always a race to see who could get its aircraft away first. One morning Leander appeared to be in front but as the dawn broke their aircraft was still sitting on the catapult at a very acute angle. Unfortunately as the crane was about to lift it off and drop it into the sea someone failed to release the locks (aircraft to catapult) with the result that the plane was stretched until something let go, and the aircraft leapt up and landed back on the catapult with considerable damage. We won that round!

Regulations demanded every aircraft had to have a daily inspection each morning before flying, and the inspection form had to be duly signed and recorded. As the hours mounted it had to have additional inspection until the time came when the engine had to have a complete overhaul. This time came whilst we were in Wellington, so here was my chance to carry out the necessary engine change at Rongotai. We carried a spare engine on board soldered up in a tin box inside its wooden case – moisture proof. I sought extra staff to assist as we had to have the craft back on board the following day. The assistant worked well until five o'clock arrived, and he disappeared. I had no option but to work all through the night and had it running by daylight ready to fly back to the ship.

Some Exciting Times

We were tied up at Suva when we received orders to proceed at haste to assist in the evacuation of Singapore. We broke the speed record to Port Moresby but there fortunately we were ordered back to Auckland as the Japanese had control of the seas further on and the risk was too great, the sea was believed to be mined.

We were about to sail from Wellington on a Friday 13 th (no ship ever liked sailing on a bad-luck day) and our black cat “Clubs”, who was victualled as crew, failed to come back aboard. He was quite old and possibly passed away. He was advertised for with nil results. Most of the crew were sure something bad was bound to happen, but nothing did. I am no longer superstitious.

Divisions (Church Service)

These were always most interesting and enlightening. On Sunday morning everyone had to parade in No. 1 Dress. R.C. and Jews were exempt including those on watch. The Marines band played the hymns. The Captain gave a short sermon and then he would address the company on what we were supposed to do, and where we were going.

Action stations always caused me some concern as I was always frightened that I might be locked in below deck. I always kept a pair of overalls and a life jacket on deck so that at night I did not have to get dressed to go up on deck.

I got one hell of a fright. I had been ashore on overnight leave. Early in the morning as the liberty boat was leaving Admiralty Steps for the ship it was using a mooring line to turn the boat around when somehow a sailor got his leg caught in the mooring line which unfortunately cut his leg off. He sat up on the stretcher and requested a cigarette.

Entertainment

At times it could be quite boring on the ship and we always looked forward to any entertainment. Occasionally a movie was screened on the waist of the ship on the deck – not much room. One would go along early, about one hour before the show, with a seat of some sort and a drink of water, as it got mighty hot as a side-screen was erected to make it dark enough to see a film.

Uckers was a popular game (similar to Ludo). For competition a 3” dice was used and the whole ship company would turn out to witness the finale.

There was a very good communication system throughout the ship. Not only was it used to issue orders but was very popular as entertainment such as very amusing records like Tommy Trinder.

All birthdays were announced as this was an invitation to have a sip of friend's rum – a very popular pastime.

Rum (up bubbly) was measured out at 12 o'clock mid-day – quite a ceremony – issued to each mess and measured out very precisely. If you decided not to have a rum ration you were paid three pence a day instead of. It was very essential that the rum ration was taken, not only as a drink. It was a very necessary asset as one could borrow or beg for a tot of rum.

The crew during the time I was aboard –

Pilot Flight Lieutenant Henry Higgins

(Replaced by Pilot Officer Johnnie McGrane)

Navigator

Wireless Operator Petty Officer Peter Lupton

Writer Corporal Mac McRay RNZAF

Rigger Corporal Squiffy Dawson (I never knew his Christian name)

Engine Mechanic Corporal Eric Ford RNZAF

Radio Mechanic LAC Jim Maitland

Bill Sykes, past Navy pilot, transferred back to England before I joined the ship

Interview Continues....

When I interviewed Eric on the 28th of August 2003, I asked him to elaborate on a few points that he'd written about in the article as transcribed above, because his view of the war, as an RNZAF man on board HMNZS Achilles, is an almost unique perspective. Although some of the following reiterates what Eric wrote above, there is also additional information and more about his career in the RNZAF after his days at sea. Here are a few questions and answers;

Dave: What countries did you visit? Do you remember all the countries?

Eric: Oh well, we never knew, they didn't tell you. We were just floating around out in the ocean. But we went to a lot of the islands like Fiji and Samoa, and all those up there. They were checking out to see if there were any Japs hiding. We never found any. Because we used to shoot this aircraft off, and have a look round, and I believe the Japs never realised we had an aircraft on board.

Dave: Did you ever see any Japanese aircraft flying over?

Eric: No, no, never saw a thing.

Dave: While you were on board ship did it ever get sent after German raiders, or was that too late in the war?

Eric: No, we never saw any raiders.

Dave: How much flying did you personally get to do in the Walrus? Did you go up very often?

Eric: Yes, quite a bit, but not very often. You know, we used to run it ashore, and we used to take all the duty free cigarettes and grog. Because there was no Customs to check us. And we used to fill her up! Of course you could buy cigarettes, we used to pay five pence for a packet of twenty cigarettes, and we used to smoke like troops because it was so cheap.

When I went onto the ship, I got a cable in Wigram to say to report to the Air Base up there, the marine base [probably Hobsonville] . You didn't know what you were doing, you just went – had to give your rail ticket, and away, off you went. And I had a look down there and I saw this Walrus thing, sitting on the tarmac, and I thought, “By God, that'll never fly!”

Anyway, I was away in it the next day. Stayed the night there and was off the next day. And we landed alongside the ship, out in the harbour, and they lifted us in. And the guy in the aircraft had to hook on – up on the mainplane there was a little sling up there, and you had to put a safety belt on, but there was nowhere to hang on! You're all adrift. And the guy in the crane was very clever. He up and threw you over the catapult, he'd lower you down the catapult, and they had six block-and-tackles across under the undercart, and they'd all hook them on quick, and that pulled the aircraft onto the catapult. Because if it was rolling at sea, you couldn't hold the aircraft. Anyway, I got on ship, and they said “There's your hammock, that's what you sleep in.” I didn't know what to do with it! But I got plenty of help. The biggest problem was to get in the thing without falling out the other side. Anyway, I soon mastered that, and they're fine things to sleep in and work forever.

We were allowed 18 inches to sleep in, and that's all you need because once you got in the hammock you didn't need any room. And you all went backwards and forwards together so it didn't matter. The feed was very good, you were never short of anything to eat. We got four meals a day, real English stuff, it was breakfast, lunch, tea and dinner. Now tea - that was quite an important meal - they usually made some scones or something like that, and you'd get a cup of tea. And then you'd get dinner at night.

Dave: On board a ship there are shifts of people, like a night shift and day shift, but did the Air Force people only do the day shift?

Eric: Yes, they did. And I must tell you about the Sunday service too. Every Sunday you had to go to Divisions, they called them, and you all lined up in your best mocker and they'd say, “Fall out the R.C.'s and Jews!” And what they did I don't know, but they possibly had to go back to work! We looked forward to the church service because they told us where we were going. That was the only time they ever spoke. The Captain, he took the service. By the way there was 600 on board.

Dave: Gosh, I didn't realise the ship was that big.

Eric: Well it wasn't, but they all had a job. I don't know what they all did, but they were cleaning and practicing all day long.

Dave: If the aircraft was always being craned off into the water, what was the catapult for? Was that just for emergencies.

Eric: Oh, well that was only if we didn't need to shoot her off, but we shot her off most of the time.

Dave: Oh right. So what was that like, going off on the catapult? You must have done that?

Eric: Yes, I have been. But I was mostly getting it ready, because we had to start it up, put it out the end of the catapult, and the motor was going flat stick and they'd fire her, and it was 10 pound of cordite, I think it was, to fire her off. And boy, did she go off in a hurry! It had to be flying by the time it got to the end of the catapult, and since it got to the end, all the legs underneath collapsed automatically.

Dave: It must have been quite a scary thing to do for the first time.

Eric: Yeah. I always felt a bit sorry for the pilot. The last one was only 20 years old, he was only a boy. But in the crew there was a pilot, navigator and wireless operator. And if she was armed it had two machine guns on her, and it could carry two 100lb bombs.

Dave: Were the Walruses noisy?

Eric: Oh yes. No mufflers, well, that's why I'm deaf.

Dave: Even when you were inside the aircraft with the engine behind you, was it still quite noisy?

Eric: Yes, yeah it was. I had to get up, and I had to fuel her before daylight. It took quite a while. And the rigger, he sat in the cockpit watching the petrol gauges, and he was supposed to tell you when it was getting full. Nine times out of ten he'd go to sleep. But he had to wind the inertia, you know, inertia starters, well you got in the cockpit and you switched it on. And we had a little mag to start it with, and he'd sing out “Switch on, contact!” and you'd switch it on see, and with a bit of luck it would go. But if he'd already overfilled the tanks and your pants were full of petrol, which happened quite often, you wouldn't switch it on. And the poor bugger had to wind it up again! You know, it nearly killed you to wind that thing up.

Dave: Was the Walrus a good aircraft? Was it always reliable?

Eric: Yes, very reliable. Very. I saw one crash. We were up in Noumea, and we were with the Leander, and she had the same equipment as we did. And we were doing dawn patrols and of course it would always become a race as to who could get the aircraft away, and they always seemed to race us. And anyway, one morning – you had to release all these legs so that you could lift the aircraft up on the crane and they'd drop it in the water. And they're heading about in front of us, and somehow or other, they didn't pull one of the releases, and up it goes, and it stretched and stretched, and it jumped off the hook. And it come down crashing on the oleo leg, and the oleo leg went right through the hull. What a mess it was. Anyway, they just dropped it over into the coal pit there, and left it there. It might be still there as far as I know.

Dave: Did you carry many spares on board?

Eric: Yes we did, we carried an engine, a complete engine. And it was sealed up in a box, soldered in, in a tin box inside a wooden one. And you had to change it, as you know, at certain hours, and we were due for a change. And I thought how the hell do I get this changed. Of course you weren't allowed to fly them if they'd gone over time. And I thought oh, we're going into Wellington, I'll get a hand in there. And I made arrangements, and they said yes we'll supply you with a mechanic to give you a hand. And this boy was good, and we worked all day, and got it back in. And come five o'clock he's off. He said “I've finished… five o'clock.” And he buggered off home! Anyway I worked nearly all night, finished it off, and come daylight in the morning I had her running and they come and picked her up, and away we went. We just left our other motor there and they, I don't know where they overhauled the Pegasus but I think it might have been Wigram.

After I come off there I applied to transfer to Hamilton where they had the major overhaul. I worked in there until the war finished. I had a good time because I was a Sergeant by then and I was in charge of part of it. But we must have overhauled hundreds of engines, one after the other, and we had a mobile test-bench on the back of a GMC truck. They came in, put the engine on the back, and drove out to Te Rapa. They had to get out of town, it was too noisy. And they run it for eight hours, back in, get another one, and away they went again. And that was continuous, to get them all done.

Dave: Where was the overhaul section? Was that right in town?

Eric: Yes, right in the centre of town. And the building now is at Mystery Creek.

Dave: Getting back to when you were on the ship, what sorts of things did you do in your spare time? Did you have any spare time?

Eric: Well, not really. If you had something to do there was always something you had to do.

Dave: But it never got boring?

Eric: Well, it did a bit, but you always gave somebody else a hand or something. Like the parachute packer, give him a hand. He was a Naval boy, and they shot him ashore to learn to be a parachute packer, and back again. That was it. But on the ship you had nowhere to store anything. It was all cupboards and that, with everything in it. But it was good fun.

Getting back to the RNZAF Hamilton maintenance facility Eric says:

But the workshop was a proper chain system, you know, they dropped the engine, and someone took it out, and then it went to the Cleaning Bay, and cleaned everything. They put it on a two-tier tray that had wheels – the whole engine on there, everything. Then you'd go on a bit further and they'd split it up – the cylinders would go to the Cylinder Bay, and get all the valves done, and the front end would go somewhere else… and then it would all come together again. They used to have a Viewing Bay, and every part went through there, and they inspected everything and measured everything, and if it was no good it got a red spot of paint on it – that's it, to be never used again. But they were very thorough.

Dave: It's very interesting.

Eric: Yeah, well it was to me too. I learned a lot in the Air Force. I had a trade and was fully qualified, but you still learned a lot in there.

My grateful thanks go to Mr Eric Ford who gave up his time and leant me several items in order to complete this page.

________________________________________________________________

Above: A scan from a sadly delapidated snap of the Achilles' Walrus. Eric is sitting in the cockpit on the far left of the

photo next to the sailor. Photo: Eric Ford

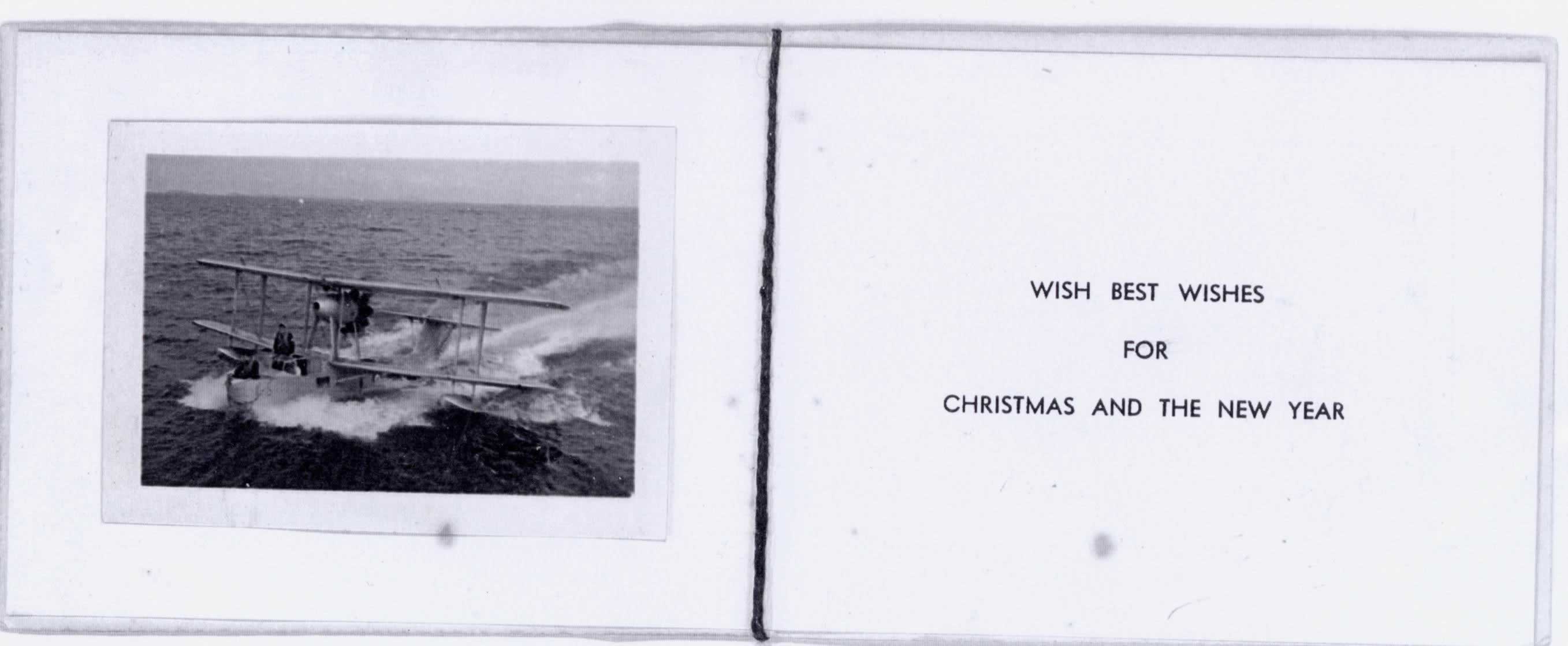

Above and below: A special memento, a Christmas Card fromn 700 Catapult Squadron, of which Eric was a part

whilst serving on HMS Achilles, with a photo of the Walrus inside. Courtesy of Eric Ford

| Home | Airmen | Roll of Honour |

|---|