_

______________________

Harold Lane THOMAS QSO

Known as Hal

Serial Number: NZ /A391850

RNZAF Trade: Pilot

Date of Enlistment: 17th of December 1939

Date of Demob: 1944

Rank Achieved:

Flying Hours: 1170hrs 10 mins (military flying)

Operational Sorties:Date of Birth: 7th of October 1917, in Cambridge

Personal Details: Hal was the son of Harold Tahana Thomas and May Elizabeth Thomas (nee Matthews).Hal was born in Cambridge whilst his father Harold senior was away at World War One. His mother May was staying in Cambridge with her friends George and Enid Taylor through her pregancy and the birth. George and Enid were the parents of Don Taylor who co-incidentally would later also be a No. 485 (NZ) Squadron pilot and Cambridge airman.

Hal's daughter Julie says, "My Grandfather was away in WWI when Dad was born. Pop had left his pregnant wife to go and fight in France. Granny Thomas went and stayed with the Taylors in Cambridge while he was away, and Dad was named Harold after his father and Lane after George Lane Taylor." So Hal's early life was spent in Cambridge, but Julie adds, "When Dad was two, Grandpa came home, injured, gassed by mustard gas, and the family moved back up to Auckland."

Leaving Cambridge at that young age, Hal grew up in Auckland and was pretty much an Aucklander apart from a short time at Waitaki. He was educated at various schools including at Mt Eden, Mt Albert Grammar and Waitaki Boys High School. Before the war he'd studied at Victoria University in Wellington to become an accountant in his father's well-known firm Maple Furnishing Co. in Auckland. It was at that point that war broke out and he joined the RNZAF.

Though he didn't return to Cambridge at all in early life Hal did not sever the connection to the town altogether. He later married Cambridge girl Thelma Browne who was a WAAF, and today members of the Thomas family are still in Cambridge, including Hal and Thelma's son Graham, and grand-daughter Sarah. Hal had four children; as well as Graham there is his eldest son Richard, daughter Julie and well known television fishing show host Geoff Thomas. Richard was named after Hal's squadron mate Richard "Dickie" Bullen, who was killed on No. 485 (NZ) Squadron's first mission over occupied Europe.

Julie Thomas says her father Hal was very close friends with Phil Coney, father of New Zealand cricket captain and TV and radio presenter Jeremy Coney, through his childhood and RNZAF career. She says, "They started school together when they were five, roomed together in Wellington, went on the same war course and sailed to England together. Phil flew bombers and made it home, although many of their friends did not, and they stayed friends till Dad's death in 1991."

Service Details: Hal had signed up to the pre-war RNZAF Reserve, in case the war erupted. He was in Wellington at the time of war being declared and he made himself available for service there. He officially joined in December 1939.

He trained initially on No. 4 War Course at No. 2 Elementary Flying training School, RNZAF Station New Plymouth, making his first flight in a de Havilland DH60G Moth on the 16th of January 1940. The Moth had been impressed into the RNZAF from the Marlborough Aero Club and still wore its civil registration at that time of ZK-ADA, but it later was redesignated as NZ514. His initial instructor was Pilot Officer Paterson, with Flying Officer Arthur Britton (also a Cambridge Airman) also acting as check flight instructor. During his initial flying training Hal gained experience on various marks of the DH60 Moth, plus he also flew the DH82a Tiger Moth biplane and the Miles Hawk and Miles Magister monoplanes.

Hal moved onto No. 2 Flying Training School next, making his first flight in the much larger Vickers Vincent biplane NZ337 on the 10th of April 1940.

________________________________________________________________

No. 4 War Course, RNZAF Station Woodbourne, 1940

Back Row, Left to Right: |

|||

Airman Pilot |

Service No. |

Hometown |

Killed |

George Montgomerie Marshall Maurice Richard Clarke R.E. Fotherington Ian Laurie Reid Mervyn Evans Henry Augustine Dobbyn |

NZ391841 NZ391824 NZ3918__ NZ391846 NZ391832 NZ391831 |

Marton Wanganui Auckland Auckland New Plymouth Auckland |

30 July 1941 Survived Survived 3 July 1941 24 July 1941 25 Feb 1942 |

Middle Row, Left to Right |

|||

C.C. White T.M. De Denne G.H. Francis Phillip R. Coney R. Webb F.J. Steel W.H. Burtwistle |

NZ3918__ NZ3918__ NZ3918__ NZ3918__ NZ3918__ NZ3918__ NZ3918__ |

Wanganui Hastings Auckland Auckland Levin Napier Auckland |

Survived Survived Survived Survived Survived Survived Survived |

Front Row, Left to Right |

|||

Allan Gerald Sievers A.G. Shaw Harold Lane Thomas Arthur Joseph Hyams John Rae Hutcheson Oswald Arthur Matthews N. Blake |

NZ391848 NZ3918__ NZ391850 NZ391837 NZ39967 NZ391842 NZ3918__ |

Wanganui Hamilton Auckland Wellington Lower Hutt Wanganui Christchurch |

Survived Survived Survived 25 June 1943 Survived 7 July 1942 Survived |

He qualified as a Service Pilot on the 27th of July 1940, just as the Battle of Britain was beginning in the UK.

As Hal Thomas left New Zealand he began writing a letter to his family that would become a diary of his voyage. His daughter Julie has kindly supplied a copy of the letter, which we can now read here to get the story in his own words:

FOR KING AND COUNTRY

I’m sending this diary back to New Zealand with a steward who will post it for me in Auckland sometime before Christmas; that’s if the old Akaroa is not held up enroute and makes it safely back. I have no doubt that most of my previous letters home have been censored but this missive should be safe enough so I will try to describe our trip in some detail.

August 10th 1940

The Akaroa left Lyttleton at 6am, this morning, Sunday August 10th 1940 and it was with mixed feelings that we watched the shores of New Zealand disappear over the horizon an hour later. For many it was a sudden moment of truth, saying goodbye to weeping loved ones and not knowing if, or when, we would see them again. There was not a great deal said during that last hour as we stood on the deck in the chilly mist and rain, all eyes glued to the fast receding hills of Lyttleton harbour. Although we were excited by the adventure that lay ahead and keen to get on with the job awaiting us in England, we all felt that the greatest thrill of all lay in store, namely the day when our homeland was sighted again on the horizon. I have settled in very well and am delighted to find about five of the chaps I went to school and Varsity with are here. Some are bound for Spitfires, some for Lancasters and some for Fleet Air Arm.August 17th 1940

The ship was ploughing through a storm for the first five days and the Captain told us that such weather invariably puts 75% of the passengers to bed. However not one pilot was ill and there was no sign of a meal missed, much to the steward’s amazement. There was a severe system of fines for missing meals at our table and that may have had something to do with our outstanding sea legs!

Shipboard life is a doddle compared to the exhausting eight months we’ve spent in camp at Blenheim, months of continuous flying and difficult exams, and we all agree that this is probably why the time at sea passes very slowly. We may have needed a bit of a rest but we’re also fit young men on our way to fight a war.

I spend much time up on the bridge and have taken several shots at the sun with a sextant; this marine navigation is as fascinating as our own aerial branch of the subject. Last Sunday was Harry Dobbyn’s 21st birthday and as we crossed the 180° meridian that day, we had two Sundays and Harry had two birthdays!August 21st 1940

Sam, Bob and I were in the chart room just before Pitcairn Island appeared this morning and it was a memorable sight to see this little rock, just a mile square, appear right over the nose of the ship after steaming for eleven days and covering 3500 long miles.What can I say about Pitcairn? I sent a letter home just for the novelty of using the Pitcairn envelope I’d purchased from a native for seven pence. The island is a desolate spot with little apparent vegetation, although the oranges grown here are simply delicious. The natives barter their carved wooden ornaments, fruit, walking sticks and other goods for money or anything you’ll exchange with them. I bought a curious walking stick for Grandpa and a good supply of oranges. We all found it most amusing to see natives paddling out to the ship wearing pullovers and scarves made of Air Force Blue and knitted by none other than Mrs Caldwell and her lady friends in Blenheim. She used to give all the pilots pullovers and scarves and of course the boys who’ve gone ahead of us by this route have apparently traded their surplus woollies for fruit.

We left an Englishman and his wife and young child there. He is going to be a temporary Commissioner for six months and we certainly felt sorry for his wife, who is a wonderful woman, as she was lowered over the side of the ship in a sling to begin an exile on that bleak spot. The sea was a magnificent royal blue, as a result of the colossal depth, about five miles apparently, and this combined with a glorious tropical sunset did provide an unforgettable vision as we sailed away.

August 25th 1940

After leaving Pitcairn the weather has settled and becomes hotter each day. There is a sudden abundance of flying fish and they make a remarkable show on a calm sea. The arrival of brilliant sunshine has heralded the long awaited start of sunbathing and swimming in our fine tiled pool. In fact, the sunshine is slowly turning me a chocolate brown colour! We are also playing a great deal of deck tennis (at which Sam and I remain undefeated champions) deck bowls, golf and other games. Each day is our own apart from a half hour of physical training in the morning and we spend extra time in the gymnasium and doing some turns around the deck, a complete circuit of the promenade deck equals a mile. The ship has a first class library and I do a tremendous amount of reading. Sam, Bob and a Wellington lad and I play contract bridge every night, I have acquired a certain amount of skill and find it a most enjoyable game. We’ve had three movie nights which were very well attended and hope for more. The Akaroa is a wonderful sea boat and a most comfortable vessel. I have a great cabin with all conveniences and I’m treated in the best manner by a most attentive steward. We feast on a continuous supply of ice-creams and pineapples and agree it is, so far, a most remarkable trip.August 31st 1940

We sighted land early this morning and spent the rest of the day running up the gulf. It was a welcome sight to see the lights of Panama in the twilight as we sailed past the town. We were so close we could see the people dancing in the hotels! Balboa is really an American suburb of Panama and it was here, in the muddy entrance to the canal, that we tied up.It was very disappointing not being allowed ashore, the New Zealand government apparently being afraid of trouble, although the American Consul had arranged for us to be escorted around the town. A local American sent four barrels of light American beer to the boat and we had a lively party tonight. We have a Maori boy with a wonderful singing voice and quite a few guitars and as a result there was a great deal of singing, much to the delight of many of the Americans who came down to hear our songs and witness our attempts at the Haka. The heat is intense and we were all bathed in sweat due to the beer we consumed. I have to say I couldn’t live in the tropics and I spend my nights sleeping on deck in a deck chair.

September 1st 1940

We entered the canal at 11am and began one of the most interesting days of the trip to date. In the early stages the place had a deceptively quiet appearance and we passed many beautiful golf courses. However I know that it’s one of the most heavily fortified areas in the world and as we passed forts of American soldiers, one having a complement of 5000 men, and heard large bomber planes roaring overhead, I realised that the place was alive with activity. Forty American marines boarded our ship and searched for cameras etc. and also made sure that not so much as a matchbox was thrown overboard enroute. I can understand America protecting the spot as it is certainly one of the most strategically important zones in the world. The system of locks is an amazing engineering feat and the speed with which we went through was impressive. The artificial lake still has trees showing above the water line and it is a strange sight to see huge liners sailing around in a valley where formally little villages thrived. I counted thirty ships passing each other in the canal in a trip of 40 miles that took 8 hours.When we reached Colon we were met by an American battleship, searched again and the marines disembarked. We saw the Rotorua beside us and were delighted to think that our Panama mail would be on its way home to loved ones. Colon is the port at this end and the Americans have their own city adjacent, named Cristobel. We are staying here only long enough to take on 30 Frenchmen who mutinied a few days ago. Apparently their Captain is a Nazi and when France fell he issued orders to sail the ship to a French port and demobilize. But the crew, being staunch patriots, cut his throat and proceeded to Colon and placed themselves in the hands of the British Consul. They’re now going home to join General de Gaulle whom they hail as the saviour of France. I look forward to brushing up on my French!

September 3rd 1940

We have spent two sweltering days in the Caribbean Sea. We now have a complete black-out in place and the heat at night is unbearable as no air can get into the ship so we all sleep up on deck. A German raider has been spotted in this area so we are zig-zagging all day and proceeding at full steam as we have no escort.September 4th 1940

We arrived at Willemstad on the island of Curacao early this morning and spent the day taking on oil, 4000 tons apparently, which took 10 hours. This island is not much bigger than Waiheke and about the same shape. However we had our first shore leave and drove into town, about 8 miles away, in a procession of taxis. The cars were driven by natives who raced each other and drove most of the journey at around 115 kilometres an hour (about 75 miles). This is a Dutch town and the people refused to accept sterling so our helpful driver changed our English money at the rate of 4.5 Dutch gilders to £1 instead of the usual rate of around 8.However we didn’t buy much, instead Sam and Bob and I hired a taxi and drove 80 miles around the island for 1Guilder each. We had a most enjoyable day seeing the magnificent homes of the Dutch people and also the Shell Oil Plant. The homes are built of red brick and have lovely gardens. It seems Shell just about owns the island. The oil is brought from Venezuela (about 30 miles away) and refined at Curacao. It’s a romantic old port with a cosmopolitan appearance, having been originally Spanish, then British (in the days of Morgan the buccaneer) and finally Dutch. Dozens of small boats sail over from Venezuela and sell fruit and trinkets in the open market, of course we were all robbed left and right by the unscrupulous traders who asked exorbitant prices for anything when they saw us coming. We arrived back at the ship very tired and hot, laden with coconuts and happy to sail at 4pm for Bermuda.

September 5th 1940

I am proud to report I have made excellent progress with the Frenchmen and have talked with them for hours. Tonight we passed through the channel between Haiti and Puerto Rico. I’m told this is a favourite spot for raiders to lie in wait. With a complete black-out being mandatory and everyone very quiet, we felt fairly safe. First of all an American destroyer stopped us and this caused tremendous excitement as none of us knew that she was a neutral ship until she was right alongside. An hour later I was sleeping on deck and awoke to see a ship loom up out of the dark. It had no markings and flew no flags. We immediately reversed course and went at full speed in the opposite direction. She chased us for about an hour but we got away finally. Nobody knows what that ship was, although the fact that she chased us indicated a raider.September 8th 1940

Early this morning we arrived at Bermuda and anchored in the Roadstead seven miles from the township of Hamilton. Everyone is very exited as we get shore leave here! The Americans have just acquired a naval base and we saw an American battleship. Then the old Diomede came out to us and it was like seeing an old friend again.September 11th 1940

The days in Bermuda will live in my memory for many years. The population is only 3000 and the local people explained that they felt they were not doing much for the war and consequently took this opportunity to entertain us on a scale so lavish that it was almost embarrassing. Of course there were no American tourists in town so they threw open their huge nine story hotels to us, we lived in suites worth about 50 shillings a day for nothing. The island itself is simply beautiful, there is no other word to describe it, and they’ve set themselves up to develop a peaceful, old-world atmosphere, banning any motor traffic. All good things must come to an end and tomorrow we set sail for our final destination, and war.September 12th 1940

At 6am we left in a convoy of 14 ships, escorted by an armed merchant ship about the size of the Monterey. There’s not a great deal of danger at this stage although very strict blackout rules are in place.September 17th 1940

The convoy from Halifax joined us today. It was a magnificent spectacle to see this convoy of 30 ships appear on the horizon and when they joined us there were about 44 ships, all proceeding in even lines about 300 yards apart. Occasionally an unidentified ship appears and everyone watches eagerly as our escort dashes out to investigate it with guns all manned. She has five 6 inch guns and is a veritable fortress.September 20th 1940

We’ve commenced doing four hour watches on top of the bridge for submarines; it‘s so tiring, scanning the sea constantly! Every course of pilots that has gone to England since May has been attacked by submarines; in the convoy that arrived a month ago four ships were lost. The convoy we just missed by a few hours in Bermuda was attacked three days ahead of us and two ships went down. We had been steering the same course but immediately changed to give that spot a wide berth. Having said that, the Skipper told us that there were eight subs operating in our new area, accordingly today was slated to be the most dangerous day and we were all prepared for the alarm during the attack times, 3am to 6am and 5pm to 7pm. When the alarm did go off we all arrived at our stations in time as we’ve done dozens of lifeboat drills and we’re more than ready. However it was discovered that a large black whale had been sighted at 500 yards and it looked just like a sub. We have the boats permanently slung over the side and wear life belts all day wherever we are.September 22nd 1940

We saw the most welcome sight of the trip today when our destroyer escort arrived. There were many sighs of relief when they appeared belching smoke and we feel reasonably safe although we’ll not be out of danger until we sight Belfast.

At present we’re a long way north of the usual Atlantic trade route and are on the latitude of the north of Scotland. Accordingly the climate is much cooler and most of the boys sleep fully clothed. Everyone has a little bag packed with personal possessions which we’re allowed to take with us into the boats. A huge Sunderland flying boat arrived overhead at about 7am and immediately commenced circling over the convoy. At 11am the first sub was sighted by the flying boat and we could see her signalling and circling over the spot about a mile and a half astern. Three destroyers rushed at top speed to this spot and immediately dropped three depth charges. Even at this range we could feel the ship shake so I can imagine the sub would be rather shaken. We expected to see a ship go up in smoke at any minute at that stage! I don’t know whether they sunk that sub or not although I should imagine so. Two more were sighted by the flying boat and depth charges were brought into action.September 23rd 1940

Last night all the ships stopped from midnight until 5am and this gave the destroyers a chance to use their sound detectors, it felt very strange. This morning a Hudson bomber roared overhead and stayed with us for a few hours. We’ve also commenced machine gun watches which will be maintained around the clock.September 27th 1940

It’s now 9am and we’re running down the channel between Ireland and Scotland. The strait is only about 13 miles wide here as we’re about opposite the Clyde River. Last night was our last night at sea and we celebrated in traditional style with all the unpopular passengers being dunked in the baths. When I awoke this morning and saw good old Ireland on one side and Scotland on the other I experienced a real thrill and when we arrive in England it will be an unforgettable experience.September 27th 1940

We duly arrived in the Lough Belfast at 11am this morning and anchored about nine miles from Belfast. Ireland looked exactly as I had always imagined it, very green and dotted with small farms about five acres in size and neatly marked off by hedgerows. Apparently they’ve had trouble in Northern Ireland with British troops so we’re not allowed to land in Belfast. Nevertheless we’re very relieved to be here as four ships from our convoy, which had gone straight to Liverpool last night, were bombed and sunk in the middle of the Irish Sea! We’ve come to Belfast because our gear for repelling magnetic mines is out of order and has to be repaired before we cross the dangerous Irish Sea. Right beside us in the Lough I can see a ship which was sunk a week ago by a magnetic mine and only her masts are showing above the water. It’s a sobering reminder! Apparently German bombers raided Belfast last night and dropped dozens of magnetic mines by parachute into the harbour. Hurricane fighters and RAF bombers roar overhead all the time. Liverpool has been bombed every night for about a week now and of course we’re expecting a raid over us at any time.September 29th 1940

We sailed this afternoon and commenced the most dangerous part of the whole trip as the sea is full of magnetic mines and submarines. At the moment Sam, Bob and I are listening to a description on the radio of the raid going on over Liverpool. We should arrive there in about six hours; however we’ll stop outside the harbour until daylight and hope to get in during the day. Bob and I did the first anti-aircraft watch tonight for two hours and it was very exciting, two planes roared overhead and fortunately turned out to be our own. We will get up at about 3am tomorrow morning to watch Liverpool; they say the anti-aircraft fire is like a fireworks display. We should be able to hear it anytime now. I’ve just been out on deck and we’re passing the Isle of Man. The ship is proceeding at full speed and zig-zagging all the time, while there is not a light to be seen or a sound to be heard anywhere. Living under such conditions and being so far away from home has given me a new perspective on life. I realise that the family circle and home mean so much more than fighting and the sooner this war is over the better. All the New Zealand boys are of the same mind and the topic of conversation has often reverted to the subject of what we shall do “when we get home”, but for now there is a job to do.8am September 30th 1940

So this is England! We’ve arrived in Liverpool early this morning and what a sight, flames and smoke are belching into the sky with thousands of balloons in the air above! They had a terrible raid here and a ship alongside us was blown to pieces in the harbour. Soon we’ll be going ashore, all so relieved to have arrived safely and have the last week over and done with. Ahead of me are my first RAF station, the mighty Spitfire, and a chance, at last, to play my part in the defence of this Grand Island.

Julie Thomas adds to the above, "This diary is based on a 24 page letter written by my late father, Hal Thomas, to his family back home. It was posted in Auckland in January 1941 by Mr P Brown, a steward from the Akaroa."

Hal arrived in Britain and in mid-October 1940 was posted to No. 57 Operational Training Unit at Hawarden, where he would learn to fly operationally in modern fighters. Here Hal flew the Miles Master before converting onto the Supermarine Spitfire and the Fairey Battle for experience in front line types, even though the Battle had proven itself in previous months to be obsolete and a disaster on the front lines.

The instructors and student pilots, now Sergeants in rank, at Hawarden. The Commanding

Officer of this school, seated centre in the wicker chair, was the famous WWI ace, Ira "Taffy"

Jones. Sgt Hal Thomas is standing in the second row from the rear, third from the right.

This course was completed on the 4th of January 1941 and Hal was now ready to be posted to an operational squadron. The squadron he was sent to was No. 258 Squadron, flying the Hawker Hurricane. This was at that time largely a New Zealand unit, unofficially, with most of the pilots being from the RNZAF or New Zealanders in the RAF. Consequently the squadron aircraft all carried a logo beside the cockpit of a silver fern on a black flag, with the letters N.Z. Unofficially this was New Zealand's first fighter squadron. This squadron had reformed for the first time since 1919 on the 20th of November 1940 under kiwi RAF pilot Sqn Ldr Wilf Clouston.

Hal continued to record his experiences in further letters home to his family. Here are some more insights into his joining No. 258 Squadron and life thereafter, thanks to Hal's daughter Julie Thomas:

January 5th 1941

“At the moment the temperature is well below zero, the ground has been covered with a heavy fall of snow. I find it very hard to imagine you people basking in a sun that I haven’t seen for weeks. We have had to become used to flying on frozen aerodromes & there is quite a technique required to land a Spitfire on snow, although the landscape looks wonderful from the air. Tomorrow I will be leaving for my squadron. This is really a great event & the day we have been training for since Dec 18th 1939. I feel that the rest is up to me, for after all I have the best flying training in the world behind me, the best aeroplane in the world to fly & am fighting fit, so we shall see what can be done….the great advantage of our own branch of the service is that we can get into the fun. It is hand to hand combat. However I do not intend to underestimate the old German & I can imagine that my first few patrols next week will see me very much awake…”January 7th 1941

“However it is a great comfort to me to realise that home is still safe & secure & the memory of those happy days in NZ is the one ideal for which I am fighting. Unless we had some ideal to fight for, this business of mass murder known as war would seem so ridiculous & farcical that I am afraid I would lose my faith in everything. Forgive my ramblings & when it is all over & we have settled down again to sanity & security, we must see that no possibility occurs of this happening again…”January 16th 1941

“Of course the Spitfire is rather strange at first after those slow old planes we used to fly in NZ & it takes quite awhile to accustom yourself to the terrific speed & power…we also had to get used to the experience of blackout in aerobatics and dog fighting, it is an amazing experience, you can sense everything but cannot see a thing, just a grey mist in front of your eyes. Naturally a great deal of our training was spent in “fighting” each other. Two pilots climb up & circle around for awhile before rushing at each other like a pair of roosters, then the fight is on & the idea is to get on the other man’s tail and stay there. If you can “black the other man” without going out yourself, it is easy, as he will be vulnerable while he is blinded. We usually roll on to our backs and scream earthwards at anything from 400-500 mph in a dive, then pull out to see if the other man can climb behind you. It is not nearly as difficult as people imagine, the idea of course being to keep reasonably fit & not drink too much or you will find that you black out very often…”“We are now right into the fun...we have to be on our toes & when the call comes you rush madly to your plane & dash off the ground in formation & after that the ground wireless stations take charge & the way they direct you around the sky & bring you home in any weather, it is a great comfort…”

June 14th 1941

“I was really thrilled to be a participant in the first engagement & it was really an amazing coincidence that Gary & I should have been together at the time & were the first to sight the quarry. I was filling in for five minutes for Gary’s No 2 man. I always fly my own section & we were sent off to intercept a German bomber during those five minutes. We were lucky enough to find the German machine all right, flying just below thick cloud & we both attacked & put three long bursts of machine gun fire into him before he escaped into cloud. I was lucky enough to meet him head on coming out of the cloud a minute later & knocked his starboard engine out of action. The last I saw of him he was diving towards the sea. They picked up some survivors from a bomber the next day & presume it to be the one that Gary and I damaged, that eventually crashed. We finished the show with one confirmed victory and two machines damaged..”

In the following snippet from the Waikato Independent nespaper, which quotes from a letter that Hal wrote about the formation of No. 485 (NZ) Squadron, it reveals a little about the make up of No. 258 Squadron as well. This article was dated the 16th of April 1941:

FIGHTER SQUADRON

OFFICIAL NEW ZEALAND UNIT

PILOT OFFICER E.P. WELLS INCLUDED

Pilot-Officer E.P. ("Bill") Wells, son of Mr and Mrs Mervyn Wells, of Cambridge, has been one of 16 pilots selected from units all over England to form a New Zealand fighter squadron of the Royal Air Force, which will use 25 Spitfire warplanes purchased with funds raised in the Dominion.

Details of the squadron are contained in a letter written by Sergeant-Pilot H.L. Thomas of Auckland. He said that a squadron comprising 17 New Zealanders, two Poles and two Czechs, as well as a number of Englishmen, had its heart set on becoming recognised as the official New Zealand squadron, and used to wear the national emblem. Its one ambition was to fly the Spitfires New Zealand had bought and thus represent the Dominion in true style.

"Our hopes crashed a week ago when the official New Zealand squadron was formed and equipped with the Spitfires bought by our own little country," Sergeant-Pilot Thomas says. He explains that 16 New Zealand pilots were immediately posted from units all over England, to found the new squadron, the "baby" of the Royal Air Force.

"Imagine my surprise and delight when I found I was one of the 16," he adds. On transferring to the new squadron, he found that he knew most of the pilots, including Pilot-Officer Wells, of Cambridge.

No. 485 (NZ) Squadron members in 1941

Standing, left to right: French; Donald Stuart McGregor; Richard "Dickie" Barrett (aka 'The Jeep'); William Arthur Middleton;, Allan Shaw; Graham Howe Francis;, John C. Martin; Marcus Knight (CO); Francis Noel Brinsden; Patrick Stewart McBride; Athol McIntyre;, T.G. Smith; Bengard; Neville; Gordon Ernest Erridge

Kneeling front, left to right: George; Murray; A.W. Morton; Hal Thomas; Dickie Bullen; Bill Crawford-Compton; Jack Maney; James Kerrow "Jim" Porteous (aka 'Pranger'); Austin B. Smith; Harvey Nelson Sweetman; and Kevin Desmond Cox

On the 2nd of June 1941, Hal was flying an operational convoy patrol off the British coast in Supermarine Spitfire Vc (coded OU-N) when he and Pilot Officer Graham Francis shared a probable kill of a Junkers Ju88 German bomber.

Hal was to take part in the first mission flown by No. 485 (NZ) Squadron over enemy-held France, flying Spitfore OU-P, and he was lucky to return from that operation. Later he wrote the following article that records his memories of that fateful first op, which has been kindly supplied by Julie Thomas.

Our first operation over enemy territory was carried out on 23rd June 1941. We were given a week’s notice and as we were based at Leconfield in Yorkshire, we were briefed to fly to West Malling in Kent and refuel before the sweep over France.

Dick Bullen and I had arranged leave together to commence on the above date and we requested that, as original members of the squadron, we should be included in the first flight over enemy territory. The request was granted and our leave passes were altered to take effect on June 24th. We’d planned to visit the Corn family in Stoke-on-Trent and play golf. I had spent a very pleasant leave with them previously and had promised to return.

As Dick and I were the same seniority the C.O. suggested we tossed a coin to decide who would lead our section of two. I called tails successfully and flew as number three in the line astern section of four aircraft, the starboard flight of three flights of four, each in line astern. The most vulnerable spot in a squadron formation is the number four position in each of the three lines as most attacks are mounted from above and behind. In the event, my calling tails saved my life and I have always called tails ever since.

We flew to West Malling on the morning of the 23rd in squadron strength of twelve aircraft and refuelled before take off, planned for midday. I remember the briefing given by Stanford-Tuck, a well known Battle of Britain pilot. We were to fly as one squadron to patrol between Calais and Le Touquet on the French coast and act as rear cover for a sweep of bombers and fighters returning from an earlier raid inside France. I can still feel the intense excitement before take-off, no doubt this feeling was shared by the eleven other pilots as not one of them had been over enemy territory before. The sensation in the pit of the stomach experienced before later operations was still to come, as we’d only once been exposed to any real danger and had not yet witnessed the death of fellow pilots.

It was a perfect summer day with no cloud visible as we crossed the French coast in squadron formation, at 15,000 feet, and turned behind Boulogne on to a westerly course towards Le Touquet. I could see the countryside below us and was gripped by a feeling of exhilaration, tinged with a heightened awareness. The next turn on the patrol line was to port and I can clearly remember looking back to see Dick behind me, he was on the outside of the turning squadron at the end of the line of four aircraft. At that very moment a cloud of smoke appeared from his aircraft. He’d obviously received cannon shells in the petrol tank and cockpit. Simultaneously I heard a noise exactly like a stick dragged along a corrugated iron fence and felt my aircraft shudder heavily. There was a heavy bump behind me and I saw a ME 109 diving away inland.

My aircraft went into a steep dive and no matter what I did I couldn’t counteract the spin and regain control. My immediate thought was that I should bail out. I prepared to do so by unhooking the radio connection and opening the canopy. However at the last possible minute I managed to recover control and dived down to ground level to find myself over a small village a few miles inland from Le Touquet. I will always recall vividly the sight of a squad of German soldiers in grey uniforms standing in a village square as I approached at high speed. They all raised their rifles and fired at me but my speed saved me, although some holes were later found in the fuselage. My reaction was to fly as low as possible on a northerly course across the English Channel. We’d been told to fly right over the water if separated as this would make it difficult for an enemy fighter to fire at our aircraft. It’s necessary to depress the nose right on sea level to line up a target directly ahead. However I was vulnerable to an enemy fighter diving on me even at sea level.

Then I noticed that the port wing had been damaged by a shell and was cut off at the aileron, with about three feet having been lost. The effect of this was not apparent at high speed but I knew it would adversely affect my stalling speed and I had no option but to land at a higher speed than normal. Just as the White Cliffs of Dover appeared ahead I observed large splashes in the sea around me and looking up I saw a Spitfire climbing away. The pilot, a Pole as it turned out, had mistaken me for an enemy aircraft, probably because of the square wing effect on my port mainplane, which had been completely changed in appearance. Unless he recognised me I was in very real danger of being shot down and there was nothing I could do about it. Suddenly he waggled his wings to indicate that he’d identified me after a second look and then flew beside me until I reached the aerodrome at Hawkinge, just behind Folkstone.

The sight of the White Cliffs is something I will never forget and that feeling of relief when I finally arrived over Hawkinge is impossible to describe. The realisation that I would not be a prisoner of war, at least on that occasion, and that I was still alive created a feeling of gratitude and appreciation of my great good fortune in escaping death, by the merest fraction, has remained, perhaps, the most significant experience of my life.

My radio was out of action, damaged by the cannon shells that had hit the fuselage and I was not able to call up sector and advise them of my intention to land at Hawkinge. However I circled the aerodrome twice before making an approach and the fire wagon and ambulance moved out towards the perimeter on the down wind boundary area. They could see the damage to my port wing and were prepared for a crash landing if necessary. I approached at 130 m.p.h. instead of the usual 90 m.p.h. over the fence and wheeled on to the grass, cut the switches and finally stopped my bumpy run just short of the boundary fence. My Polish friend landed beside me and was the first to greet me when I stepped out of the cockpit. He apologised most profusely for firing on me over the channel and failing to identify me.

I fell on to the grass and smelt it, never has anything smelt better and I just lay there for awhile enjoying the luxury of being alive. That feeling has never left me and every 23rd July at 12.20pm I’ve stopped what I was doing and just taken my thoughts back to that moment when I saw Dick Bullen die as he hit the ground and I prepared to bail out of my damaged aircraft.

An American film crew were at Hawkinge that day filming any damaged fighters or bombers returning from sweeps over France. USA were not in the war at that stage and the films were for display in America to encourage an appreciation of what was happening to RAF aircrew engaged on missions over enemy territory. They filmed the aeroplane and myself and I still have a print of the crease in the tail and where a cannon shell had entered the fuselage and been deflected by the armour plating behind my back. From time to time, if I believe I have a problem, I find that it is good therapy to take out this photo and the problem shrinks into insignificance.

I received first class treatment that afternoon. After a medical inspection to establish I had not been wounded I was looked after in the mess for two hours. My station in Yorkshire was notified that I’d landed and a special aircraft, a Blenheim light bomber, was allocated to fly me back to Leconfield. I landed there about 6pm and the squadron had landed after re-fuelling at West Malling. They knew of my escape and of my report of Dick’s death. The remaining ten pilots chased the 109 that had fired on Dick and myself but were not able to catch him because of his speed built up in a dive. They’d seen the Spitfires go down out of control and had feared the worst for both of us. Needless to say we had a wake that night, as Dick had been a very popular member of the squadron and I, having witnessed his death, felt the effect of it more than the others.

The following day I was flown to White Waltham, an aerodrome near Maidenhead west of London, in the Blenheim that has brought me from Hawkinge. I decided to take my week’s leave as arranged and Tuska McNeil came with me in place of Dick. We took the train from London to Stoke-on-Trent and the Corn family met us and drove us to their beautiful home. They were wonderfully kind people and Tuska and I had a memorable leave. Two things stayed with me particularly and I suspect that I felt things keenly as a result of Dick’s death. Firstly, the very large table in the dinning room where Mr Corn sat at one end and his wife at the other and Tuska and I on each side. They usually had a huge vase of flowers in the middle which virtually obscured Tuska from my vision and vice versa. During a long meal, served by at least three maids for only four people, I may not see Tuska for an hour although we conversed merrily through the barrier of the foliage. And secondly, the Corn family owned a large company manufacturing porcelain ware, ceramics, bathroom and toilet equipment. The bath and W.C. in our suite had inlaid fish in the porcelain sides and old Tuska, who was a sheep farmer from the backblocks of the East Coast, had never seen anything like it before. He spent long periods with a book in the bathroom as he was entranced with the equipment that was such a contrast to the facilities at home. I still remember how amusing I found all that.

Here is another fascinating piece written by Hal about flying night patrols in No. 485 (NZ) Squadron Spitfires

Night Operations

Four pilots were assigned for night operations during fighter nights and flew to Church Fenton which was a night operational station. When enemy aircraft were plotted, one pilot was scrambled and we normally drew lots for order of take-off. The flight could last two hours and two operations would be the normal maximum per night. The fighter nights were arranged during a period of raids on Hull and on three consecutive nights the city was on fire as raids were mounted each night.

On the first night Bill Middleton flew the first take-off and he was scrambled at about 2100 hours. Just as we heard his engine open up for take-off the phone rang and the controller asked us to stop him taking off as a Whitley aircraft had crash landed on the runway with a full bomb load. We were not able to stop Bill and we waited for the impact should he hit the Whitley. He was just airborne when the crash was heard and his aircraft ploughed into the bomber scattering bombs and petrol while his Spitfire broke its back. We jumped on to the fire wagon and arrived at the scene with the ambulance. Fortunately there was no fire and Bill was removed from the wreck conscious. He was very lucky as he only suffered a broken knee cap and was taken to York Hospital where he remained for some weeks. He rejoined the squadron two weeks later and was shot down over the channel on his second operational flight.

My turn came two nights later and I was sent off at about the same time. The runway lights were very dim and visible only under 250 feet. There was no margin to line up the nose of the aircraft and the most difficult problem to overcome was the exhaust flame on each side of the cockpit. The Spitfire was totally unsuited for night flying because of the high nose, lack of visibility forward when landing and fragile undercarriage.

I entered cloud immediately on take-off and climbed on instruments through 6000 ft of what seemed like thick black cotton wool. On breaking out of the cloud I was almost overcome by a feeling of loneliness that is hard to describe. Beneath me was a white sea of cloud and above a clear sky with a brilliant moon and stars. The only other sign of human existence was apparent in my shadow tracing my flight path across the sea of clouds.

I climbed to 20,000 ft and levelled off at a point 100 miles out over the North Sea. The controller called me up on the radio and gave me a compass heading to fly to intercept what he described as 90 Plus bandits (enemy aircraft). At this range from the nearest German airfields they could only be bombers heading for a raid on one of the major cities in the Northern part of England. The only hope of seeing them would be to pick up the red exhaust gases from their engines as we had not got interception radar, as carried by later aircraft designed for night operations.

It is not possible to describe the feeling of being completely cut off from any contact with another person; the sheer overpowering feeling of absolute solitude was an experience I will never forget. I could imagine Charles Lindbergh felt the same way when crossing the Atlantic on his solo flight. However he faced thirty-three hours compared to my two hours, although I had 90 plus enemy aircraft in my vicinity that would see my exhaust flames well before I could pick up theirs. They carried special fittings to reduce the glare and our later fighters were fitted with “fish tail” covers on the exhaust outlets to reduce the glare.

In the event I was not able to locate the bombers and was ordered to return to base. During the next half hour I was completely in the hands of the controller to provide me with the necessary course to fly in order to avoid balloons which were concentrated in the industrial areas. I was given a course to fly which would bring me over a location on the map 30 miles from the aerodrome. Should my radio become unserviceable, I was under orders to fly due west until I estimated I was across the coast and bail out. That was a prospect which was regarded with concern by every pilot and more frightening than bailing out in daylight. However the alternative did not exist as the whole countryside was blacked out and navigation was not possible without a navigator (as carried by bombers) and the danger of hitting balloons was very real.

The controller directed me to the map location where a truck was positioned with a flashing light which was turned on when I was overhead at 3000 ft. The flashing beacon flashed in Morse, two letters at set intervals. I knew the course to fly from that spot for five minutes to bring me over the aerodrome at 2000 ft. Every evening the truck was driven to a different location and the flashing letters were changed each night. In that manner enemy aircraft were not able to locate the aerodrome should they pick up the lights flashing.

When I was over the aerodrome after five minutes of flying a known course at a given speed, the controller gave me a course to fly and reduce speed and height, to line me up on a lighting system that would be turned on at the right moment to produce a tunnel down which I would fly to approach the runway. The lights on the runway were visible only below 250 ft and I would be over the place before I could see the flare path to land on.

The tunnel, known as the Drem Landing System, consisted of several 40 gallon drums holding lights spaced in an inverted cone and at a fixed distance apart for a mile from the runway. Once they were turned on, when I was flying down wind at the mouth of the tunnel (at its widest point), I turned across wind and knew that I had to fly down the tunnel, losing height at 300 ft for each light. I had lined up at 1500 ft, and as there were four lights on each side, I should be at 300 ft on the aerodrome boundary. At that time the dim lamps of runway lights would be turned on. I would be lined up to see them ahead and could land on the runway.

Should enemy aircraft be in the vicinity when we arrived over the aerodrome the lights would not be turned on and we would be instructed to climb to 5000 ft and bale out. The success of such an operation to bring a single engined fighter home from a spot 100 miles out to sea, and at 20,000 ft, is dependent on the pilot having complete confidence in the ability of the controller to provide the correct courses to fly. These came from the plots of the aircraft given to him by the plotting stations using radar.

The absolute loneliness of the pilot of a single engined fighter at night is something experienced by very few during the war. The daylight flights were always flown in squadrons and sections of at least two and other pilots were visible and we could talk to each other by radio. Bomber crews at least had company during the night flights and this was a very real factor in providing confidence in each other and allowing them to face danger. Later night fighters were two engined and carried two airmen, a pilot and a navigator/radar wireless operator.

The operations described above were, to me, the most incredible experiences of my five years of flying in the war and I still look back with astonishment when I think that I flew for 500 miles at night in complete black out up to 20,000 ft and returned to an aerodrome which was also in complete darkness and landed on a runway with a flame path visible only under 250 ft.

Added to the above problems was the fact that the Spitfire was never meant to be landed at night because of its design, whereas the Hurricanes with perfect forward vision and a strong wide undercarriage, was made for night flying. But we flew what we had to, with what we had.

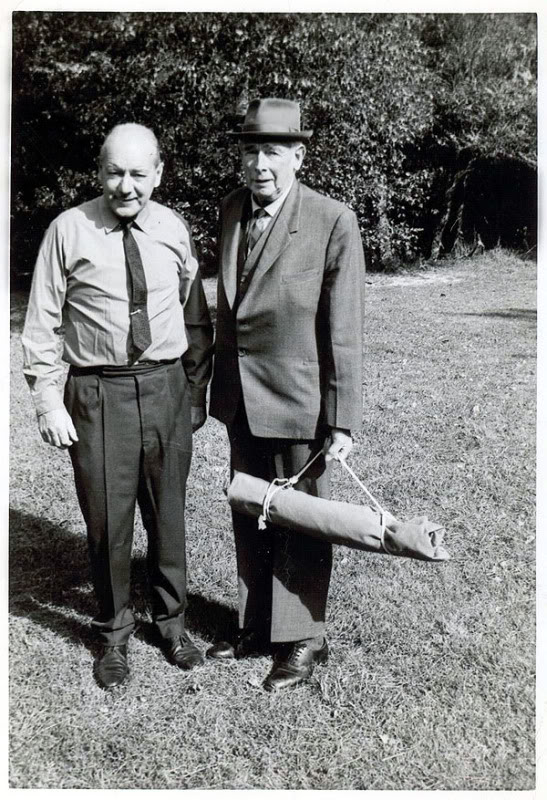

Above: Hal Thomas with his wife Thelma and daughter Julie on the occasion of when he was awarded the Queen's Service Order, for services to the Air League

Hal with his friend Leonard Isitt, the former Royal New Zealand Air Force

Chief of Air Staff

Date of Death : 21st of July 1991

Cremated: Hal was creamated and his ashes were scattered into Lake TaraweraConnection with Cambridge: Hal was born in Cambridge, married a Cambridge girl and has family still in Cambridge

| Home | Airmen | Roll of Honour |

|---|